Local solutions: traditional foods to stave starvation

8 August 2025

The phrase “necessity is the mother of invention” could not be more aptly applied to what is currently taking place in Sudan. Over half of Sudan’s population—25 million people—is experiencing acute hunger. Malnutrition, especially among children in Sudan’s conflict areas, is desperately high. Over 40,000 children were admitted for treatment for severe acute malnutrition in North Darfur State within the first five months of 2025, the UN reported, double the number for the same period last year. The World Food Programme (WFP) says it has been unable to deliver aid for over a year to the besieged city of El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur State.

But amid conflict and a dearth of aid, Sudanese men and women continue to search for ways to save the lives of children. Okra flour, also known as “weyka,” has become a lifeline for those who recognise its nutritional value in treating malnutrition among children, with the addition of locally available ingredients.

Zeinab’s recipe

The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) besieged the Al-Fateh neighbourhood of Omdurman, one of the three cities in the Sudanese capital, from July 2023 until the army recaptured the area in March 2024. Trapped in the conflict, mothers like Zeinab Omar, 28, had to find creative solutions to keep their families alive. Zeinab recounts how a simple habit she inherited from her mother saved her life and the lives of her two children. “Since I got married, I used to cut a quarter of okra into small slices, then spread them out in the sun to dry. I did this in the hope of using them later in cooking, until I always had a plastic bag full of okra.” She continues, “My husband would get angry and ask, ‘What’s the point of it?’ He loves fresh okra for cooking, but with the intensification of the siege and the lack of supplies in local markets, this okra became our only refuge.”

Zeinab would gather firewood and whatever was available and affordable in the scant, costly markets in Omdurman. “What saved us—my children and I, the oldest of whom was not yet three years old—was the weyka dish with the fish my husband caught,” Zeinab recounts.

In Umm Dafso, an open market that has miraculously survived despite constant bombardments, Zeinab noticed skyrocketing prices: a kilogram of corn flour had risen from 1,600 Sudanese Pounds (roughly 60 cents) to 30,000 Sudanese Pounds ($11).

Today, Zeinab looks at her two children, whom she describes as healthy, playing and laughing despite the crisis. She smiles and says, “My husband now, when he leaves the house, he comes back carrying okra!”

Zeinab was not alone in her experience of siege. Families faced hunger alone in many areas of Sudan, including Khartoum, Darfur, and Kordofan. Malnutrition rates, particularly among children, sharply increased in these besieged areas.

“Community food adaptation”

According to UN data, over 2.9 million children are acutely malnourished, with 729,000 children under five suffering from Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM), which represents the most life-threatening form of hunger.

“In times of siege, displacement, or even in remote villages lacking medical supplies, we always need to turn to what is local and available. Weyka is a traditional food with high nutritional value, especially when used in children’s meals,” says Dr Mamoun Abdelhalim, a paediatrician and therapeutic nutritionist formerly at Bahri Teaching Hospital.

Dr Abdelhalim told Ayin he saw many families suffering from food shortages while working at the hospital, including weak children who had lost their appetite. In some cases that did not require urgent medical intervention, he would simply advise mothers to include ingredients such as weyka, millet, and peanut butter (“dakwa”) in their daily meals. The doctor stated that these ingredients do not treat severe malnutrition, but they do help replace vitamins and minerals and improve the efficiency of the child’s digestive system.

Describing what Zeinab did—drying and storing okra—he said it was a very clever act and an example of what we call “community food adaptation”. In such isolated environments, where therapeutic foods like “raw foods” or even fortified milk are not available, okra can be part of a “life-saving meal,” especially when combined with other protein sources like lentils or fish.

“Weyka contains fibre and antioxidants, helps strengthen children’s immunity, and improves nutrient absorption, which is very important for children suffering from diarrhoea or chronic infections,” he added. Dr Abdelhalim says governments and non-governmental organisations should innovate, support such community initiatives, and develop simple nutritional recipes based on what is already available in Sudanese households.

Popular treatment with scientific support

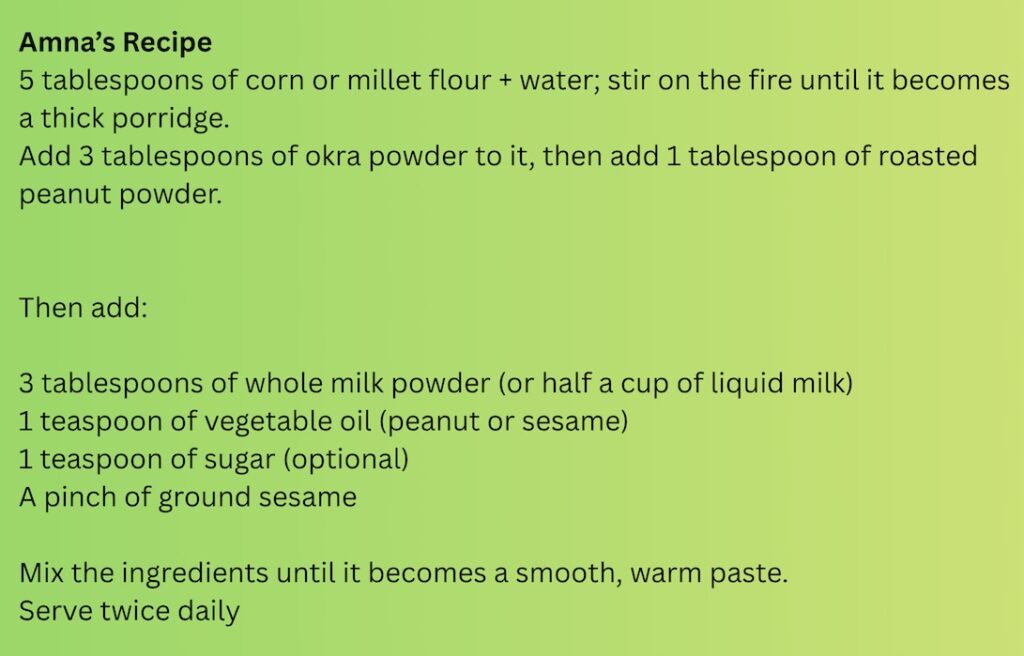

Zeinab’s recipe—without scientific awareness—and what the doctor suggested are very similar to what Sudanese nutritionist Amna—a pseudonym—is doing today. She works with a volunteer initiative that provides alternative therapeutic meals to children suffering from mild or moderate malnutrition.

Amna, who has years of experience in community food supervision, noticed the widespread availability of dried okra in households and devised a recipe inspired by locally available ingredients, mimicking the nutritional value of imported medicinal products.

“The idea came from our reality, from what is available in Sudanese homes. Weyka is rich in plant-based protein, fibre, and antioxidants, and it helps improve digestion and nutrient absorption. If we add milk, ground sesame, and a little sugar, it turns into a complete meal suitable for children.”

“The idea came from our reality, from what is available in Sudanese homes. Weyka is rich in plant-based protein, fibre, and antioxidants, and it helps improve digestion and nutrient absorption. If we add milk, ground sesame, and a little sugar, it turns into a complete meal suitable for children.”

Amna warns that salt is not suitable for children under one year of age and warns against adding it. She also emphasises that these ingredients do not replace therapeutic nutrition, but they contribute to improving the general condition and serve as a realistic solution in the absence of supplies.

Okra cultivation…a solution awaits

For such recipes to become a sustainable solution, the availability of the basic ingredients must be ensured, and here the importance of okra cultivation becomes clear. At the pesticide market in Ad-Damar, Hisham Mohammed Bala, a pesticide dealer and farmer, says okra is an ideal crop since it is available year-round, having two planting seasons.

It is also a highly productive crop, Hisham adds. “One acre can produce between 3 and 6 tonnes, depending on the variety and planting date,” emphasising that “continuous picking of pods—i.e., continuous collection—increases flowering, which leads to increased production.” The harvest begins after one to two and a half months, depending on the season, and continues for approximately two to three months. But there are also challenges, he says, not least several pests, such as the whitefly and the Egyptian thorny worm, that target the plant.

Like Dr Abdelhalim, Hisham believes humanitarian organisations and local authorities should consider investing in okra as a locally grown solution to stave off both the current and impending famine. “If any party wanted to work on transforming the weka into a real therapeutic food, the resources are available, the soil is suitable, and the farmers are ready,” he said. “If only there were an entity that adopted the idea and implemented it in a scientific manner.”