South Sudan, Sudan’s army, and the RSF: a delicate balancing act

5 October 2024

In a bid to keep oil flowing, the mainstay of South Sudan’s economy, the country has maintained a diplomatic balancing act with its restive northern neighbour, Sudan. Without taking sides in Sudan’s ongoing civil war, now 17 months in duration, South Sudan has tried to maintain relations with both warring parties, Sudan’s national army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces.

As both warring parties control critical pipelines and refineries, taking sides with either Sudanese fighting force would be economic suicide for Juba.

“South Sudan now has to grapple with the difficult task of staying on good terms with both of Sudan’s main belligerents—the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo “Hemedti” and the army headed by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan—so that neither turns against it,” according to the think tank, International Crisis Group.

But individual relationships between South Sudanese officials and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), along with an RSF encroachment into mineral-rich, disputed border territories, may affect Juba’s delicate balancing act, analysts say.

Kiir meets Burhan

South Sudanese breathed a sigh of relief following news of a possible resumption of oil exports after a meeting in mid-September between President Salva Kiir and Sudan’s de facto leader, the Chairman of the Sovereign Transitional Council, Lt.-Gen. Abdel-Fattah Al Burhan.

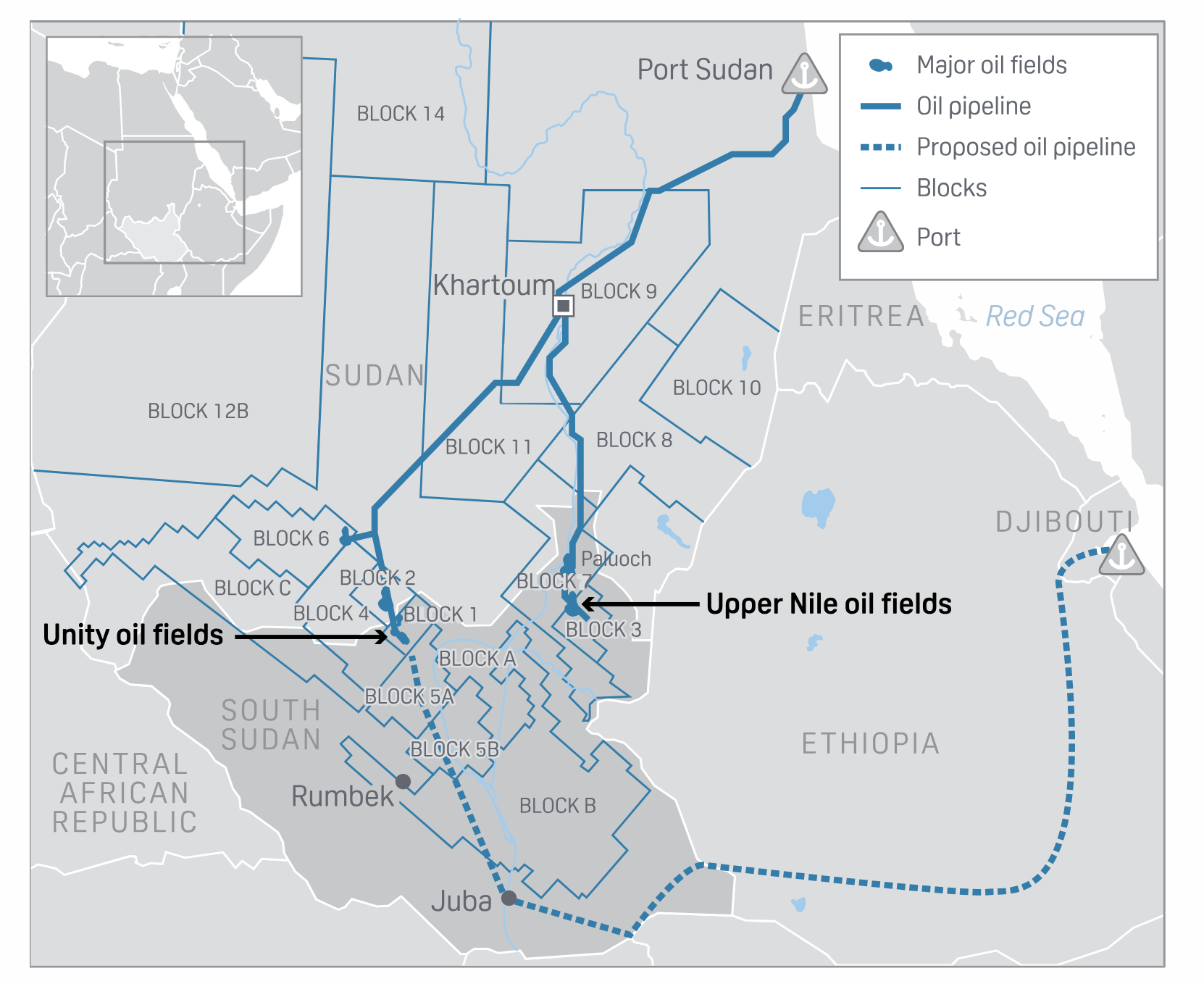

This is because South Sudan relies on oil exports through Sudan’s pipeline, refinery, and Red Sea Port to fund up to 98 percent of its budget—revenue that has been missing since February after Sudan issued a force majeure on the export of South Sudan’s oil following a rupture in the oil pipeline in a Rapid Support Forces (RSF) controlled territory. South Sudan’s crude is mostly pumped from the Upper Nile oil fields to Bashayer Port in Sudan’s Red Sea state via a series of six stations, several of which are now compromised as a result of the conflict.

The halt of oil flow has had severe economic repercussions after the pipeline’s rupture seven months ago. The lack of pumped oil has led to seven months of unpaid salaries for civil servants and skyrocketing inflation of over 107 percent.

When Al Burhan landed back in Port Sudan after his one-day impromptu working visit to Juba, Sudan’s acting Foreign Affairs Minister Hussein Awad said in a statement that the two sides agreed to remove all obstacles to transporting South Sudan’s oil through Sudanese territory.

“A joint committee between the two countries’ oil ministries will be formed to develop an operational plan to resume pumping South Sudan’s oil, in addition to agreeing to transport humanitarian aid to South Kordofan State via Juba International Airport,” Awad said. Similarly, like his Sudanese counterpart, South Sudan’s Foreign Affairs Minister also told reporters that the export of the country’s crude oil would resume in the weeks ahead.

The reality on the ground, however, remains less straightforward from what the two heads of state agreed. Many key oil facilities remain under RSF control, making their security a major concern, according to the former Undersecretary of the Sudanese Ministry of Energy, Hamid Suleiman. “Burhan and Kiir’s agreement’s success hinges on resolving the conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the RSF. Without a ceasefire or agreement between the two warring factions, it remains unlikely that oil transport can safely resume,” Suleiman said in an interview with Radio Dabanga.

South Sudan’s military support

According to an analysis by the Sudan War Monitor, one critical aspect of Burhan and Kiir’s meeting, however, was not publicised: the Sudan army’s request for military support. Burhan is seeking the help of a former rival against a new one. “Sudan’s military leader is seeking Juba’s cooperation in military matters–including supply routes to South Kordofan for the dry season fighting,” the Monitor reported.

Among several other issues, RSF supporters suggest that the SAF probably wants to reinforce and resupply a handful of besieged military units in South and West Kordofan states that border South Sudan to the north. Pro-SAF elements from the two Kordofans say even civilians in Hegleig, Babanusa, Dilling, and Kadugli risk starvation if they cannot be resupplied.

Burhan is also eager to repatriate several hundred Sudanese troops that recently retreated from West Kordofan State into neighbouring Northern Bahr al-Ghazal State, South Sudan, says policy expert Akol Dok.

In the case of Hegleig, troops can be re-supplied directly from South Sudan by road, but for Kadugli and Dilling, soldiers supporting Sudan’s army cannot arrive safely without permission from the rebel forces in South Kordofan, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – North (SPLM-N). Humanitarian access talks between SPLM-N and the army last May did not materialise despite initial positive talks in Juba. The SPLM-N later rejected an air bridge to Kadugli and other cities for fear that the army would use it to smuggle weapons and supplies, thus a collapse of the talks.

Kiir’s government always maintained neutrality in the Sudan war; nevertheless, it has ties with both warring parties. On one hand, South Sudan has relied on Sudan since independence to transport its oil. On the other hand, several South Sudanese are fighting as mercenaries for the RSF, many of them captured in Khartoum. It is a reality Juba has distanced itself from despite the continuous publicity by SAF-affiliated media against South Sudanese as sympathisers of the RSF. This neutrality, however, will be put to the test if the army’s agenda is to be implemented.

South Sudan and the RSF

Since last year, South Sudan has provided the RSF with a fuel supply for its Darfur campaigns without the direct involvement of the government in Juba, reported the UN Panel of Experts. According to the report, the RSF secured a fuel supply route from Juba to Wau on a weekly basis. “From War, fuel was transported in civilian cars such as land cruisers to Raja, then to RSF-controlled areas in South Darfur, through Kafia-Kingi,” the report said. “While local South Sudanese officers, such as some army officers in Wau, were involved in this smuggling, South Sudanese government authorities did not play any role.”

While the government of South Sudan may not have a direct relation with the RSF, individuals within the government—whether based in Wau or Juba—continue to collaborate with their neighbour’s paramilitary force, according to a government official speaking to Ayin on the condition of anonymity.

One name that emerges on top in regard to this collaboration is Tut Gatluak, commonly known as “Tutkew”, the security advisor for President Kiir. A stout figure with familial ties to Sudan’s former dictator, Omar al-Bashir and his ousted National Congress Party (NCP), Growing up with humble beginnings in Mayom, Unity State, former President Bashir took Tutkew under his wing as an adopted son and assigned him to monitor the operations of the late warlord, Gen. Paulino Matip, disguised as a translator. A staunch ally to Bashir’s regime, Tutkew helped the Sudanese army and Bashir’s former spy chief, Salah Gosh, in military and intelligence operations within South Sudan up until the latter’s independence in 2011.

Tutkew is loved and feared in Juba with equal measure. Some praise Tutkew for his role in establishing peace after South Sudan’s 2013 conflict; others accuse him of advancing Sudan’s NCP agenda within South Sudan.

Whether supportive or not, Gatluak has maintained a relatively longterm relationship with the RSF leader, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, aka ‘Himedti’. In January last year, three months prior to the outbreak of conflict in Sudan, Himedti warned Tutkew’s family to leave the area, according to news reports. “He told us to leave and go to Egypt, and some of our family members returned to Juba,” a family source was quoted as saying. Tutkew and Himedti have met on several occasions, including a meeting with Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar just days before the war commenced and mediation talks over the disputed Abyei region.

This year, SAF claimed at least 4,000 South Sudanese fighters linked to the RSF were killed in clashes in southern Khartoum. The hired South Sudanese fighters, the same source claims, belong to Tutkew and operated under the command of the notorious warlord Thomas Tel. Tel, commonly known as “Balat,” is believed to have led South Sudanese mercenaries during an attack by the RSF on the Armoured Corps in Khartoum last August.

“The Juggler”

In Juba’s political circles, he is unofficially known as the “super juggler or Mr. Fix,” a phrase coined after he maintained favourable relations with Ethiopia and Egypt despite the Dam-related rivalries between the latter. In August 2022, he brokered a security cooperation agreement with Ethiopia to jointly fight terrorism, armed groups, and organised crime in the region. In the same month, he struck a similar deal with Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sis, in which the president affirmed his country’s keenness to maintain security and stability in South Sudan.

It still remains to be seen, however, whether Tutkew can perform a juggling act that meets the interests of Sudan’s warring parties and ensure South Sudan resumes its critical oil exports through Sudan.

RSF in Raja

RSF’s ongoing presence in the Raja County region, a mineral-rich border area between Sudan’s South Darfur State and Western Bahr-el Ghazlal State in South Sudan, could pose another challenge to Juba’s delicate balancing act. Local residents of the county fear the RSF’s presence is linked to exploiting the mineral reserves within the area and may be long-term.

So far authorities in Juba have remained silent over the RSF’s presence in the area, a silence potentially linked to South Sudan’s tightrope walk, where too much visible support to either warring party in Sudan could lead Juba to fall off the rope.