Catholic NGO boss accused of racism and abuse in Sudan

29 October 2020

This investigative story was originally produced and published in The New Humanitarian on 22 October 2020. The story is re-published with permission.

In the wake of George Floyd’s death and the Black Lives Matter protests that followed, Catholic Relief Services told its staff it was launching an initiative to stamp out racism within the NGO, one of the world’s largest charities.

Soon after, its American boss in Sudan sent staff a reminder for the launch. The same day – 28 July – he was arrested on a charge of verbal abuse for calling a security guard a “slave”.

The allegations of racism weren’t the first against Driss Moumane – at least three whistleblower complaints had been filed against him, dating as far back as 2018, according to a six-month investigation by The New Humanitarian that involved interviews with several former and current employees.

“This guy humiliated me and my colleagues for over a year and a half,” Mustafa Babikir Abdullah Ali, the 22-year-old security guard, said during a September interview. “When I saw the police arresting him after I opened the case, I was very glad.”

In July, the Baltimore-based Catholic Relief Services (CRS) spokesperson Nikki Gamer would not say what – if any – action had been taken on the previous whistleblower complaints against Moumane, or whether there had been other complaints against him during his previous CRS postings. But eventually, by 20 October, Gamer confirmed Moumane’s employment with CRS had been terminated, offering no other details.

“CRS has robust systems and procedures in place for receiving and responding to fraud, safeguarding and other performance-related allegations, including appropriate disciplinary and corrective action,” Gamer said. “We can now confirm his employment with the agency has been terminated.”

Moumane did not respond to emails and calls for comment.

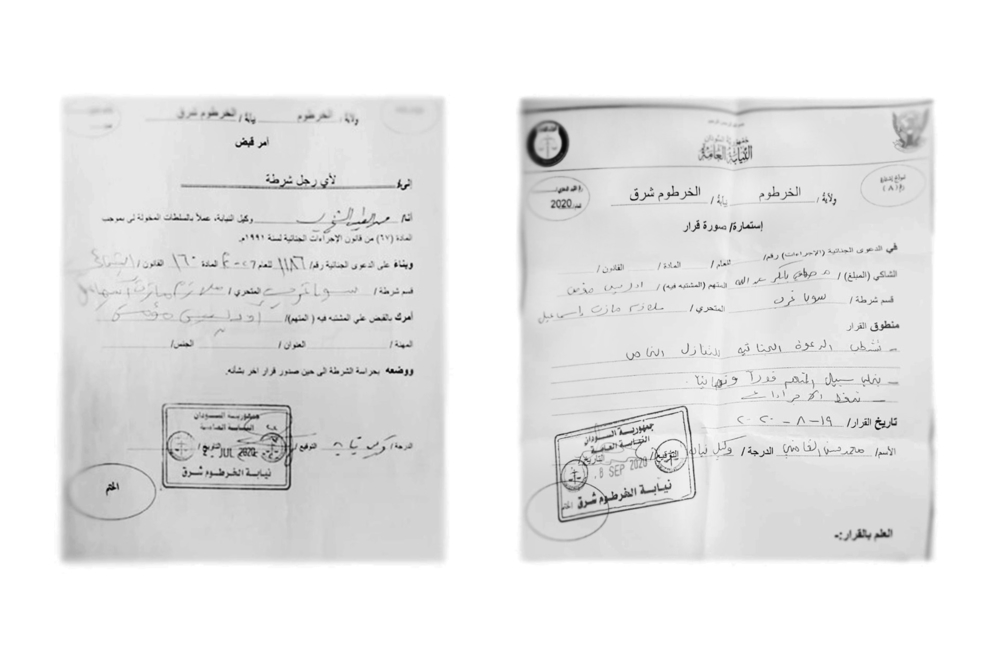

Arrest then charges dropped

In April, a whistleblower accused Moumane of racism, abuse, and misconduct as early as 2018. The same whistleblower claimed he had also been pushed out of his job for making the complaint. The New Humanitarian (TNH) investigation then followed a circuitous path over several months as two more ex-CRS employees came forward with different complaints prior to the event that would eventually see Moumane dismissed.

Sudanese police arrested Moumane after he allegedly verbally abused Babikir, a guard with the Al-Hadaf security company who had been assigned to Moumane’s house.

The 20 July clash occurred at Moumane’s house in the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, after Babikir came to collect an overdue payment he said was owed for extra cleaning duties.

When Moumane didn’t pay him, things became heated.

“I was very angry, so I hit the door”, and in the row, Moumane shouted, “I don’t like this slave, take him out!” according to Babikir.

Ismael Gamar Aldin, another guard assigned to Moumane’s property, said he witnessed the altercation. Gamar Aldin said Moumane had also previously shouted at him.

The derogatory use of the Arabic word for “slave” to refer to black people in Sudan is not unusual.

Babikir said Moumane would also ask him to perform duties that fell outside his normal work, such as cleaning up dog excrement and prevented him from using the toilet.

Moumane is a US citizen of Moroccan heritage, according to a police officer in Khartoum who said he had seen his passport – he spoke on condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorised to speak publicly about the case.

Babikir’s attorney, Salim Mohamed, told TNH the charges were eventually dropped after Moumane apologised and made an $800 payment. Two senior officials from the security company were also present during the meeting, Babikir said.

The payment was not for additional work he had done, Babikir said, noting that he only made the equivalent of $15 per month as a security guard.

A driver and a police officer who spoke on condition of anonymity also said a payment had been made as a condition to drop the case.

“CRS has not made any payments related to Mr Moumane’s case and has no verifiable knowledge of any payment made to settle this case,” Gamer said in a 16 October email.

Sudan’s humanitarian aid commissioner for Khartoum, Mustafa Adam, said the regulator had not received a complaint from Babikir but would still consider legal action against any NGO should a complaint be raised.

“We are very keen to maintain the dignity of the Sudanese people as well as respecting the international humanitarian laws,” he said.

Status, pay, and power

Shortly after George Floyd’s death in late May, CRS President Sean Callahan made a public commitment to tackle racism, saying it could “do better to pro-actively combat systemic racism wherever we find it.”

CRS, like many NGOs, has been updating its position on racism. On 2 September, it announced the appointment of a new “chief of people and diversity” for its workforce of some 7,000 people.

“The story actually isn’t that the guy called the other guy a slave, it’s that he’s in the position to do so, and with what consequences?” said Adia Benton, an anthropologist whose studies at Northwestern University in the United States.

Babikir said that CRS staff and police advised him not to pursue his case against Moumane.

“They all told me that this guy is an American, so he is powerful, so it’s better for me to accept the settlement and take the money,” he said.

The status, pay, and power of expatriate aid workers typically offers a degree of immunity and sense of entitlement, according to Angela Bruce-Raeburn, regional advocacy director for Africa at the Global Health Advocacy Incubator, a US-based policy NGO.

“There’s a certain pervasive sense of power and superiority that comes with these jobs,” Bruce-Raeburn said.

In a 31 July email, Gamer said the charity takes “any and all allegations of racism or prejudice extremely seriously.”

With revenue of some $940 million, CRS is the largest charity that falls within the orbit of the Caritas confederation, a global network of more than 160 Catholic charities. Together, they handle around $2.35 billion per year.

Sources of income include donations from church-goers, corporate donors, and governments. Caritas members are not funded by the Vatican, but donations are sometimes made by the Pope to contribute to specific projects.

‘The cruel reality of power’

Douglas La Rose, a white American from California, was one of several employees in Sudan who signed a joint whistleblowing complaint in December 2018 – accusing Moumane of “favouritism and cronyism, neglect, abuse”.

“The story actually isn’t that the guy called the other guy a slave, it’s that he’s in the position to do so, and with what consequences?” — Adia Benton, Anthropologist at Northwestern University, USA

The complaint accused Moumane of staff endangerment, and of threatening to dock the pay or otherwise punish those who asked to protect their families during Sudan’s 2018 political upheaval, which led to the ouster of President Omar al-Bashir after 30 years in power.

The complaint also alleged misuse of CRS resources, including a claim that Moumane kept two office cars for himself and his wife even though transport was limited. It also alleged that Moumane regularly ridiculed the accents of staff, berated workers for their performance, and showed favouritism to those he had previously worked within other CRS postings.

Moumane reportedly also worked for CRS in the Central African Republic.

After filing the complaint, La Rose said he was told in May 2019 by Matt Davis, the East Africa director at CRS, that his position as business development manager was being restructured within the region. La Rose said the position was filled four months later – in Sudan.

Davis did not respond to an email asking for comment about the complaint or Moumane.

La Rose said CRS had fostered a “culture of privilege” by recruiting “mostly white Americans” as “fellows” – one-year entry-level programmes that open the door for staff positions within the charity in the United States and, often, overseas.

“This creates a kind of special class within CRS of fellows who understand that the sky’s the limit for them,” La Rose said. “These people will do everything in their power to protect each other. It is always very clear who was or wasn’t a fellow, and people who come into CRS outside the fellow track are treated as expendable.”

One female staff member said she went to Moumane to report sexual harassment by another expatriate CRS staffer, her supervisor.

She said Moumane told her she would risk her job if she reported it officially. The complaint noted both her supervisor and Moumane, the NGO’s Sudan representative.

Her written complaint alleges that she was then moved to another department where her contract was not extended soon afterwards, adding that the experience left her with “real psychological problems”. The CRS human resources department looked into the formal complaint she filed in November, but she said they didn’t take any action as they said there were no corroborating witnesses.

A third former CRS worker said the same expatriate supervisor had also sexually harassed her. She said she told CRS human resources staff that the man had made “inappropriate comments”, but she never received a response.

The same third worker also filed a complaint against Moumane, accusing him of bullying and favouritism, and accusing him and one of his close senior staff of racism. Like the others, she believes her employment was discontinued because of making the complaint.

“I tried to be a whistleblower, but nothing happened,” she said.

Two of the former CRS staff spoke on condition of anonymity to avoid any repercussions with future employers. TNH also spoke to two current employees in the region who echoed some of the same complaints against Moumane. They also spoke on condition of anonymity.

“Addressing systemic racism and institutional power disparities is a challenge even for those who are in higher positions,” La Rose said. “The cruel reality of power and privilege at the highest levels comes crashing down on you in unimaginable ways. Before you have finished telling your story, your bags are packed and your name blacklisted.”

CRS did not answer questions about the whistleblower complaints, or about the allegations that people were sacked because of their complaints, only acknowledging that some of the allegations spanned “a period of time”.

“Within this time, CRS has refined its approach to receiving and responding to allegations in tandem with the progress made across the sector on these matters,” Gamer said, without specifying what, if any, changes had been made.

Sudan operations funded by US, UK

CRS is one of dozens of aid agencies that work in Sudan to help with the country’s recurrent food insecurity, issues relating to conflict and displacement such as in the western Darfur region, and climate-related crises ranging from drought to floods.

East Africa is the charity’s biggest operational area, taking up about 30 percent of its spending in fiscal 2019. CRS is also the lead agency on a five-year, £48 million project funded by the UK government in Darfur – CRS receives about £5 million a year for its role.

Many of CRS’s programmes in Sudan are funded by the UK government, and by the US government department in charge of humanitarian assistance, USAID.

USAID has inked projects with CRS in Sudan with a value of about $13 million in 2020.