Hassahisa: Amid a displacement crisis, community support key to survival

10 July 2023

When Rania Fadul and Mohammad Ibrahim’s little white Hyundai Accent broke down along the road between Khartoum and the neighboring city Medani, it was strangers who brought them fuel and directed them to shelter in nearby Hassahisa.

And as their money ran low, community members who didn’t know them gave food, beds, and toys to their four kids – two girls and two boys. Even just beyond the borders of a city under attack, people were offering what they could to help.

“Help was coming from the locals along the road,” Ibrahim said. “You will find them every 20-30 meters along the road until you reach Hassaisa. They were giving people cold water and food. May God help them and protect them.”

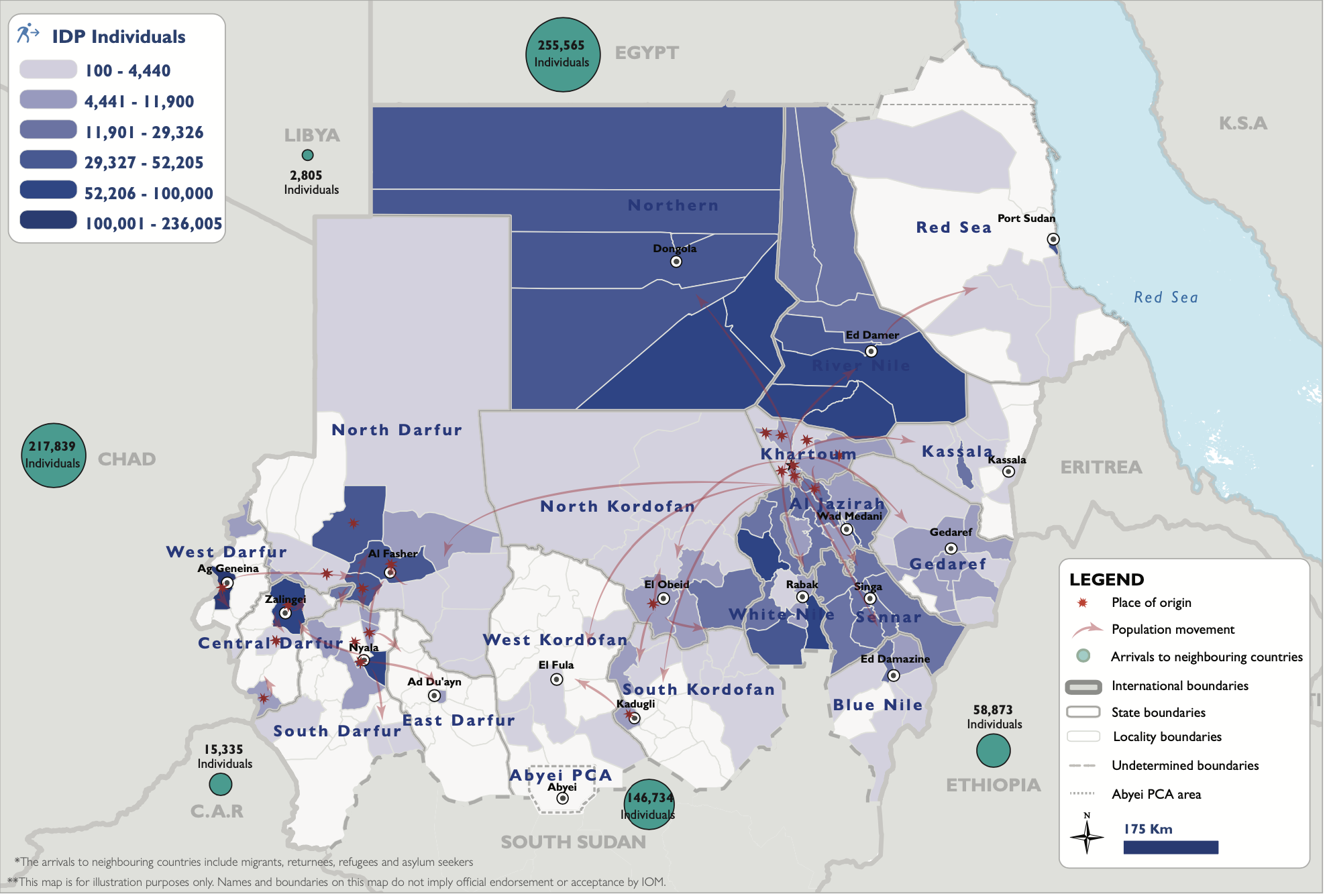

Since the conflict broke out in April, an estimated 3 million people like Fadul and Ibrahim have been displaced to other cities, states, or countries, according to data from the International Organization for Migration’s Displacement Tracking Matrix. Of those people, more than two-thirds are coming from Khartoum – and many of them are now staying in the homes of friends or family, and receiving support from people they don’t even know.

At the Alhilla Al Jadida neighbourhood school in Hassahisa, about 150 kilometres from Khartoum, the classrooms are now packed with families with nowhere else to go. Ibrahim’s family ended up there with the help of a citizen committee in Hassahisa. The community in the Alhilla Al Jadida neighbourhood donated beds, mattresses, covers, and set up a food schedule to ensure the families caught in the fighting could feel some comfort.

“We have been through this before,” said Afrah Mohammed, as she served tea in the mid-morning to some of the families staying at the school. Since the war began, she’s been there nearly every day, early morning preparing tea, beans, or lentils for breakfast as the day goes on. The food is donated by the neighbourhood committee, established to help as the crisis worsened. They’ve also brought charcoal, flour, sugar, and anything else the families need.

Afrah’s family is from Absya Tagli in South Kordofan, a region along the border with South Sudan. She said her family has also had to leave their home community. “Until now we are still not settled,” she said. That’s why she’s committed to preparing food for the families, even as prices increase, and more people arrive. Since the conflict started in mid-April, prices for basic commodities have doubled, and in some cases even tripled.

“I have been there before … we survived.” She said she remains optimistic and faithful that the families – hers included – will one day be able to return home.

Before April 15, when the fighting broke out across Sudan, the country already hosted more than a million refugees – many from neighboring countries South Sudan and Eritrea. Most were living in camps, out-of-camp settlements, or cities across the country, especially in Khartoum and White Nile states. Now, another 2 million people are displaced – and more than 1.3 million are from the Khartoum area.

Meklit Eman was one of those refugees – and now she’s also one of the displaced. She came to Khartoum from Eritrea 12 years ago. When the fighting began she was sheltering her family in their home, until the food began to run low. “My kids can’t handle the hunger, and if one of them got sick or if anything happened to them, it would be a problem,” she said. “Everything is closed. We decided to leave before the food we had ended.”

After running out of money along the journey, she met a man at the Hassahisa bus station who asked if they needed help. “I told him that we don’t have anyone here, and he said ‘You are welcome.’” The man brought Meklit and her family to stay overnight in his home, and in the morning directed them to the Alhilla Al Jadida school.

Meklit is there now with her two children and the orphaned children of her deceased sister. She’s still hoping to make it to Kassala. “Because we are refugees we can’t go back to Eritrea,” she said. She has a case being processed to go to Canada but doesn’t know how to check the status. She left Khartoum with her documents just in case she would be granted asylum.

Displacement from Khartoum has led people to many places – IOM data shows displacement patterns in all directions: some people moved north to Dongola or Port Sudan, and others moved south or west, to cities in other states like Singa, Kadugli, or Al Fashir. More than 250,000 people have crossed a border into Egypt, another 155,000 people traveled to Chad, and 120,000 crossed to South Sudan. The direction was often dictated by how much money they had, whether they could cross a border, and how easy it was to leave the city.

For Faiza Mohammed Ahmed, after hearing days of fighting, it had seemed time to risk moving, especially from her home at the city’s edge where it was easier to leave. “When the plane came we had to stay under the bed,” she said. They walked for a distance from their house in the Soba neighborhood along Madani Street.

A group of more than 10 people including her and her family members – including her children – stood in the middle of the road waving for cars in hopes that someone will stop and help them. A bus driving to Madani stopped for them, but the driver asked for more money than Faisa had.

Knowing they were desperate, people on the bus gathered together enough and donated it to cover the family’s journey. With the donated money, they made it to Hassahisa – but they knew no one in the city.

After a visit to the mosque, they were brought to a teaching center that had been converted into a displacement camp. Locals had donated beds and mattresses, and clothing. They came with milk tea and biscuits and juice and even brought the children toys to play with on the first day of Eid.

“We don’t want for anything here,” Faiza Mohammed said, standing in a stark room filled with at least 20 mattresses pushed up against the walls. The air was steaming hot and stale, and light poked through the thin tin roof. Outside, children screamed and cried on a crowded porch and open area, and other people slept on the floor amid the noise.

“Since day one these people did what they could,” Faiza added. “Our kids celebrated Eid in a way we couldn’t have celebrated. They did things we couldn’t do in our own houses… We are very happy. They made us feel like we are staying in our homes.”

That feeling echoes somewhat for Rania Fadul and Mohammad Ibrahim, but they also know they cannot stay where they are forever. “We were scared for our children’s lives, so we sought the safest place outside of Khartoum,” Fadul said, adding that their house wasn’t damaged but she was afraid the war was coming closer.

“We wish God our safety and the war stops,” Ibrahim said. “We ask God to fix this with the least damage.”

Nearly half of the people displaced by this conflict want to one day return to their homes, according to IOM data. Another third of those displaced are still hoping to move on to another place – like Rania and Mohammad.

Money continues to run low, transfer services aren’t working well, and food prices are rising. They know they can’t rely on community support forever. They want to continue moving to another city, where they have family and could start rebuilding.

“My feeling is the same as every Sudanese; I left my home against my will,” Ibrahim said. “The citizens are the biggest losers in this war.”