Sudan’s lead gold producer, exporting directly to the “enemy”

18 August 2024

This report was done in collaboration and support with the Washington DC-based global security nonprofit C4ADS.

-

- Gold is the main fuel of Sudan’s war, financing both the army (SAF) and RSF.

- Sudan’s top gold producer, Alliance Mining, is UAE-owned and Russian-managed — even as SAF accuses the UAE of backing their opponents.

- Gold production at Alliance Mining is done in complete secrecy. Staff are unaware of production levels but suspect it could be as high as 6.5 tons per year.

- Gold output 2024: 71 tons from army areas, worth $1.57B — nearly half of all Sudan’s exports.

- Up to 70% of gold exports are smuggled; 515 tonnes have been missing since 2012; 97% of declared exports go to the UAE.

- Nearly all gold produced in the arm-controlled areas is exported – whether officially or smuggled – through Egypt.

- Elites and senior military officials benefit from the gold trade and the limited oversight over it during wartime.

- The current gold trade’s advantages for elites guarantee that there will be interest in seeing the destructive conflict continue.

Gold has been the primary currency used to finance the ongoing devastating war in Sudan, and the leading gold producer sells directly to its declared enemies. The Alliance Mining and Kush for Exploration and Production Company, based in the army-controlled area bordering the Red Sea and River Nile states, has routinely been earmarked as the largest gold mining operation in the country. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), the army’s professed opponents, own the Russian-managed company. Despite having links to Sudan’s army, the bulk of Alliance’s gold exports are sent to the UAE, the same country the Sudanese government has accused of backing its combatants, the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). In March, the army-controlled de facto Sudanese government filed a court case against the UAE, charging the Gulf country with genocide for their alleged backing of the Rapid Support Forces.

Since April 15, 2023, the national army has fought a devastating war with the RSF, a paramilitary force that was once aligned with the army and deployed on the ground to fight in the vast western Darfur region. A dispute over resources and political influence, however, set the army and RSF apart, with each side relying on gold mines to fuel their war efforts. The ongoing and expanding gold operations of Alliance Mining and Kush Exploration & Production Company are yet another stark example of the multitude of complex foreign influences fuelling the conflict and exacerbating an already dire humanitarian crisis.

The Sudanese people are enduring what the United Nations and aid agencies on the ground consider the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, with some estimating at least 150,000 deaths, 12 million conflict-displaced, and half the population facing food insecurity. Overshadowed by conflicts elsewhere in the world, global funding appeals remain only 60 percent met. The warring parties frequently obstruct humanitarian aid from reaching its intended recipients. At the beginning of this year, many internally displaced persons (IDP) camps are reporting child mortality rates of nearly 12 per day due to famine.

While humanitarian aid is prevented from accessing its destination, gold flows relatively effortlessly through the country, with nearly all exports—whether smuggled or openly shipped—ending up in the United Arab Emirates. Gold exports have helped both sides purchase increasingly sophisticated weaponry, with the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) relying on China and the UAE, while the army receives support from Egypt, Turkey, and Iran.

Gold: central to Sudan’s economy and prolonging the war

While Sudan’s conflict, now in its third year, has decimated most of the country’s economy, the gold mining sector continues to thrive—even expand in the army-controlled areas. In February, the military-controlled government in Port Sudan announced record production in 2024. The state-owned Sudan Mineral Resources Company (SMRC) claimed gold production in the army-controlled areas reached 71 tons in 2024, up from 46 tons two years earlier. The Central Bank of Sudan figures show exports brought in $1.57 billion in much-needed tax revenue last year.

Given these figures, gold production is the most significant source of income for the warring parties, supporting a cross-border network of actors including other armed groups, traders, and, perhaps most importantly, external governments. Control over Sudan’s vast gold reserves is a contributing component for the conflict between the army and Rapid Support Forces (RSF), says Sudanese economist Abdelazim al-Amawy. It is also, al-Amawy says, “a key factor in prolonging the war.” Foreign countries are not only importing and trading in Sudan’s gold and providing the revenue to prolong the conflict, but they are also actively mining gold within the country. The Alliance Mining Company, owned by the UAE and managed by Russians, is a pivotal example of Sudan’s leading gold producer.

The Alliance Mining Company

The Alliance Mining Company operates along the border of the River Nile and Red Sea states in Sudan, in the Haya area, roughly 100 kilometres outside of Port Sudan, the capital of Red Sea State. The company is both historically and currently recognised as Sudan’s largest gold producer, having received multiple awards in the past from the SMRC and the Ministry of Energy and Mining.

The company also serves as the primary gold mine for the UAE-based Emiral Resources Mining Company. The last available ownership data for Alliance shows Emiral owns 68% of shares, while 25% is owned by the Sudanese mining supply company, Sudamin, and 7% is owned by Exxon Advanced Projects Limited. On its website, Emiral lists Kush as one of its holdings, alongside its subsidiary, Alliance for Mining, which it claims is “the largest industrial gold producer in Sudan”.

Alliance was originally part of the gold mining and trading company linked to the infamous Russian paramilitary Wagner Group under Yevgeny Prigozhin. By late 2024, the Wagner Group (now called “the Africa Corps”) had earned over $2.5 billion from illicit gold mining since the invasion of Ukraine, according to a report by the World Gold Council. The war profiteer Yevgeny Prigozhin originally owned Alliance Mining along with Al-Solagh Mining in Sudan. Both mining operations started with different names, Kush Mining and Meroe Gold, respectively.

But in 2022, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) bought the mining company, which continues to operate under the umbrella, Emiral Resources, according to company letters in Ayin’s possession. The UAE bought off five years of debt from Alliance Ltd and helped the company evade March 2021 US-led sanctions against Russian companies operating in Sudan. Boris Ivanov, a former Russian diplomat and executive at Gazprom PJSC, a major Russian state-owned energy corporation, founded the UAE-based Emiral Resources Company. High-level Emirati investors, including Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed, the UAE’s national security advisor, have also been linked to the company. Ali Al-Rashdi, the CEO of the Dubai-based mineral extraction company, International Resource Holding, currently serves as the chairman of Emiral Resources.

For Sudanese working at Alliance, however, the major mining operation is simply called “the Russian Company”, says one Alliance production engineer on condition of anonymity. “The name comes from the fact that it is the only company around here that has Russian people working for it,” the same source told Ayin. “Sudanese are not even allowed to access the room to see where the gold is produced.” As of 2022, the director and all of the department technical heads’ company documents in Ayin’s possession are of Russian origin.

Alliance mining: digging on the short-term

Alliance, along with most mining operations in Sudan, has relied on local, artisanal miners to do the dangerous, heavy work, according to local staff who spoke to Ayin on the condition of anonymity. Alliance and its affiliate, Kush for Exploration and Production, started mining in 2015; while registered as an industrial mining operation, its focus has always been around processing “mining waste” or “tailings” instead of industrial drilling.

The “tailings” practice prioritises low-cost, high-profit tailings with weak regulatory enforcement over actual long-term investments in industrial mining. This discrepancy may explain why the SMRC reported in 2024 that local, artisanal miners accounted for 83% of the total gold production in areas controlled by the army. In 2024, out of the total declared gold production of 64 tons, 53 tons were produced by local miners. According to the organisation SwissAid, artisanal mining dominates Sudan’s gold sector, accounting for 91.5% of total declared production.

Artisanal miners rely on inefficient traditional methods to extract a maximum of 30% of the gold from ore, leaving a significant portion of the gold particles in the residue, which is known as tailings or “Karta” in Sudan. Local miners are directly contracted to mine within the mining blocks of Alliance, as they are for other Russian mining operations, such as Wagner Group’s Al-Solagh Mining (Meroe Gold). This reliance on local miners ensures Emiral Resources an unregulated workforce that is difficult to monitor and tax, as well as track actual production rates, says researcher Suleiman Baldo. “It’s a low investment – maximum yield operation,” Baldo adds. “Equipment for processing tailings is, at most, seven million (dollars), and you are productive from day one.” This form of mining has always been associated with the elite and their affiliated armed groups. Since the war started in April 2023, both the RSF and the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) have been involved in controlling mine waste companies.

Alliance gold production

According to company records and news reports, Alliance Mining produced one ton of gold last year. The actual output is far higher, say Alliance production engineers who spoke to Ayin in confidence, whereby tens of millions of dollars’ worth of gold are sold to the UAE. The same sources told Ayin that the gold production process of collecting and refining tailings (or “karta”) is a non-stop, 24-hour process shrouded in secrecy. Out of the three main mines within the company, the company produces around 9 grams per day. If continuous production takes place, this would mean Alliance and Kush could potentially produce 6.5 tons per year. While there are no official figures available to confirm this, local employees believe the actual production figure for 2024 and now 2025 is closer to this level of production. If true, this would be double Alliance’s gold production in 2020, marked at 3.2 tons, according to data holdings from C4ADS.

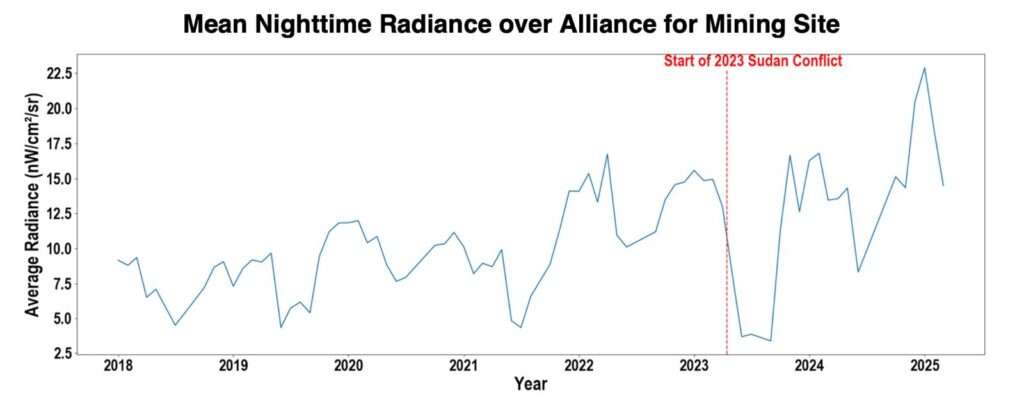

From 2024 onwards, there was a sharp rebound in production across all mining operations within the country, including Alliance. According to one of the production engineers at Alliance, the company invested in new machines this year and has expanded operations. Satellite imagery collected by C4ADS in November 2023 and in March 2024 indicates continued mining activity, judging by earth movements, small to medium excavations, and building constructions. Nighttime radiance levels measured by C4ADS in 2025 would also suggest a return to mining excavations following the pause at the start of the current conflict.

But the local community could hardly witness any increments in mining activity at Alliance, local staff told Ayin, given the secrecy that shrouds the companies’ operations. According to the production engineers at Alliance, the room designated for weighing and melting the gold into bars is off limits for local staff. “The gold is collected and melted every three days and converted into ingots,” one of the engineers said. “No one is allowed to enter the combustion chamber except the Russians.” According to the same sources, the gold is then taken at night and shipped for export away from watchful eyes. “The whole transfer is done in complete secrecy; none of us know where the gold goes from here,” the engineers added.

Mass smuggling and the UAE

According to gold researcher Mohamed Salah, most companies involved in “tailings” or “karta” mining only disclose a small portion of their production, while the majority remains unreported. By comparing the production rates listed by the Central Bank of Sudan with the actual export rates, a serious discrepancy emerges. For almost every year between 2012 and 2024, production levels are higher than exports, SwissAid reports. During this time period, authorities recorded 404 tons of gold exported while 919 tons of gold were produced, marking a discrepancy of 515 tons. SMRC director Mohammed Taher believes nearly half of the gold produced in the army-controlled areas is smuggled across borders; some researchers estimate even higher rates – closer to seventy percent. Out of the 71 tons officially produced in the army-controlled areas last year, less than half, only 34 tons, were declared on export.

The mass smuggling of Sudan’s gold occurs, Baldo says, because the state is complicit in the trade. “The government of Sudan encourages corruption. SMRC officials are complicit in the process and government authorities look the other way since they don’t pay the SMCR employees a decent wage.” The gold smuggling racket in all of Sudan’s mining sectors led Finance Minister Jibril Ibrahim to warn of the collapse of Sudan’s economy, along with the army, if this trend is set to continue.

Whether it is exported legally or smuggled, nearly all gold mined in Sudan ends up in the United Arab Emirates. In 2023, roughly 97 percent of gold exports from the army-controlled areas went to Dubai. According to data from the UAE’s commodities exchange, the small Gulf country became the world’s second-largest gold exporter in 2023, overtaking Britain. The Central Bank of Sudan reported last year that gold exports from army-controlled areas to the UAE remained consistent with previous years, at 97%; this arrangement earns the state $1.5 billion and represents nearly half of all Sudan’s exports. In comparison, Sudan exported only $1.2 million worth of gold to Turkey in 2024, $7.9 million to Qatar, $16.3 million to Egypt, and $24.6 million to Oman. According to SwissAid, the UAE represents the leading destination for smuggled gold, with at least 220 tons shipped directly to Dubai from 2012 to 2024. Even gold smuggled from other countries, such as neighbouring Egypt, finds its way to Dubai.

Egypt and Russia

While the total amount is unknown, local staff working at Alliance believe a significant amount of the gold produced from their mines is shipped directly across the border to Egypt. Sudan’s northern neighbour, a key ally in the SAF’s war effort, has earned substantial profits from gold sales in recent years, with the majority being sold to Dubai. UN trade data shows that Egypt’s gold exports were over $1.8 billion in 2023, with over half this amount ending up in the UAE.

Gold traders speaking on condition of anonymity told Ayin that over half of the gold produced in the River Nile and Red Sea states ends up in Egypt, whether exported legally or otherwise. “On the SAF side it’s obvious; the biggest smuggling route is Egypt,” SwissAid researcher Marc Ummel told Ayin. Swiss Aid estimated roughly 44 tons of Sudanese gold were smuggled across the border into Egypt last year. It is something Finance Minister Jibril Ibrahim hinted at in March this year, claiming a “neighbouring country” had obtained 48 tons of smuggled gold last year and warning that Sudan’s army would collapse if the economy collapsed. Longstanding economic liberalisation policies in Sudan that encouraged graft and looting, says economist Dr. Wail Fahmi, have weakened Treasury revenues and marked a significant loss in export returns—largely due to the smuggling of key raw materials, especially gold.

“This [the gold trade] is one of the Sudanese army’s most important incentives to perpetuate the war and prevent it from ending so that it can benefit from the corruption of these funds. These funds are not subject to any oversight and are solely managed by the army commander and the governor of the Central Bank.”

— Mubarak Al-Fadl, Head of the Umma Party, former investment minister

The Sudanese gold sold across the border is significantly more profitable due to Egypt’s favourable tax policies. According to Baldo, Egyptian and Sudanese security actors benefit markedly from these activities. Roughly 100 kg of gold is smuggled from Sudan into Egypt per day, equating to more than 66 tons from the beginning of the war to the end of 2024. “There is a whole system where Egyptians encourage gold to come to Egypt; no documentation is required,” Baldo said. “The motivation for Sudanese traders is simple: a better price and the chance to take goods [from Egypt] to wartime Sudan to make even larger profits.” According to one Port Sudan-based gold trader, gold sold in Sudan for $250,000 could be smuggled to Egypt in a one-day trip and sold for $300,000, netting a $50,000 profit in just 24 hours.

Some of Sudan’s gold goes to Egypt through the Sudanese army’s company, Zadna, says Mubarak Al-Fadl, head of the Umma Party, former investment minister, and a businessman with ties to the gold sector. Zadna International Company for Investment Ltd. exports 700 kilograms of gold per year in return for food and other army and trade supplies, Al-Fadl told Ayin. In May 2023, just weeks after the war started, Lt Gen Abdelfattah al-Burhan, the head of the army, appointed Dr Taha Hussein Yousef as the General Manager of the company. “Large quantities of gold produced in areas bordering Egypt, such as Halfa and the Red Sea, are also smuggled into Egypt,” Al-Fadl said.

No trade data exists to suggest Sudan exports gold to Russia but the Council of the European Union reported in 2023 that Russian paramilitary groups such as the Africa Corps have exported significant amounts of Sudanese gold to Moscow. According to an article from the UK daily The Telegraph, Russia had prepared for international sanctions following their invasion of Ukraine in 2022 by securing foreign gold reserves from Sudan and elsewhere. Without data to back up these claims, it is challenging to ascertain whether Sudan is exporting gold to Russia, especially since Russia’s ambassador to Sudan has denied such exports.

Contradictory trade

Given the increasing body of evidence linking the UAE’s support to the RSF and the multiple public outcries made by the army in relation to this support, the army’s ongoing gold trade with the Gulf country seems a perplexing paradox. Not only is the army trading gold with the UAE, an alleged enemy, but the largest mining operation taking place in SAF-controlled territory is actually owned by this same country, which is the primary backer of the Rapid Support Forces.

Two factors could account for this glaring inconsistency: a scarcity of options and personal greed. According to the Director General of the SMRC, Mohamed Tahir, there are simply limited options for exporting gold elsewhere. The UAE, Tahir says, has a developed financial system and a point of access to global markets. Tahir claims the government is attempting to find alternative markets in Qatar, Oman, and Saudi Arabia.

In an interview with Al-Jazeera, Finance Minister Dr Jibril Ibrahim stressed that trade and export revenue transcends any political dispute. “We’ve heard a lot of criticism about how we allow gold exports to destinations we’re in conflict with,” the minister said. “But shifting to new [gold] markets takes time, and we are currently transitioning gradually to alternative ones.”

“The army-controlled state is happy for Alliance to contribute to the state coffers, but they are also happy to share things around that are not announced.”

–Dr Suleiman Baldo

The UAE is the main destination for smuggled gold out of Africa, hosting a gold laundering system that has prevailed for years. According to Swiss Aid, the UAE has, over the past decade, accepted more than 2,756 tons of smuggled gold with a total value of over $115 billion. Despite harbouring laws to prevent gold smuggling, Ummel says that the laws are rarely adhered to, allowing a steady flow of smuggled gold into the country. The UAE is also logistically convenient for most gold traders operating in Africa. “They have big transport planes to carry the gold,” Ummel said. “Cash is still used; you do not need a visa to enter the country and can simply carry the gold by hand.”

Other global centres for gold sales, such as London and Singapore, are off-limits for Sudanese traders, Al-Fadl says, because of their selling requirements, which require traders to prove and clarify the source of the gold. “As a result, the Sudanese, including the military authorities, prefer to sell in Dubai because it is a free market, and they are able to obtain cash and dispose of it easily,” he said. Al-Fadl asserts that this also applies to Russian arms dealers who exclusively transact in cash in Dubai.

According to one Port Sudan-based gold trader, the military’s relationship with the UAE in the gold sector remains essential, regardless of political disagreements. Commercial dealings, including gold exports to the UAE, have not ceased in any way. “This whole process happens with the knowledge and assistance of military personnel—up to the rank of lieutenant general,” the gold trader told Ayin on the condition of anonymity.

With the dominance of artisanal miners and mining operations such as Alliance that rely on tailings in Sudan’s gold industry, the country remains ripe for smuggling the mineral to the United Arab Emirates. “It’s a very realpolitik environment where everyone benefits for themselves,” Baldo said. “The army-controlled state is happy for Alliance to contribute to the state coffers, but they are also happy to share things around that are not announced.” The scale of the flow underscores how small-scale, artisanal mining has mushroomed into a business involving millions of people in Sudan, producing volumes of gold far larger than full-scale industrial productions.

Senior individuals within the army and business elite help facilitate gold smuggling, according to an official from the ministry of energy and mining under the de facto, army-controlled government. These individuals, the ministerial source told Ayin on the condition of anonymity, all have links to the main mining companies operating in SAF-controlled territories, including Alliance. “There are senior people behind the gold trade who directly benefit from these [smuggling] operations,” the official said. “The current war makes these operations even easier for them with the reduced scrutiny. No one is currently watching.” The expanding gold mining operations in Sudan, combined with security-sponsored gold smuggling routes and the absence of gold trade regulation in the UAE, suggest that confusing operations like those of Alliance are likely to persist.

Conclusion

The Alliance Mining and Kush for Exploration and Production Company reveals several critical issues concerning Sudan’s current war and the gold mining industry. For one, Sudan’s current war is far from civil – a multitude of foreign actors are backing it up and providing devastating longevity, partly through their interest in the gold trade. Not only is gold the mainstay of Sudan’s export economy, but it is also a key resource both warring parties rely on to fuel the conflict. Both sides, including the army and the RSF, rely on the UAE in this process. And while both warring parties continue to hinder aid access, causing widespread starvation across the country, gold continues to find markets, and production appears set to expand.

The majority of Sudan’s citizens are yearning for peace after enduring over two years of one of the worst humanitarian catastrophes in the world. But there are senior individuals within the armed forces and government who benefit from the status quo via current gold smuggling operations. “This is one of the Sudanese army’s most important incentives to perpetuate the war and prevent it from ending so that it can benefit from the corruption of these funds,” Al-Fadil says. “These funds are not subject to any oversight and are solely managed by the army commander and the governor of the Central Bank.”

If this concern is not addressed, more gold will flow from Sudan to international markets in the UAE, ensuring both warring parties continue to access more weapons and more war. “This is not a war of ideology; it’s a war of resources – the warring parties and their international backers are fighting for resources for the country,” says Baldo. “It’s that simple, and that callous.”