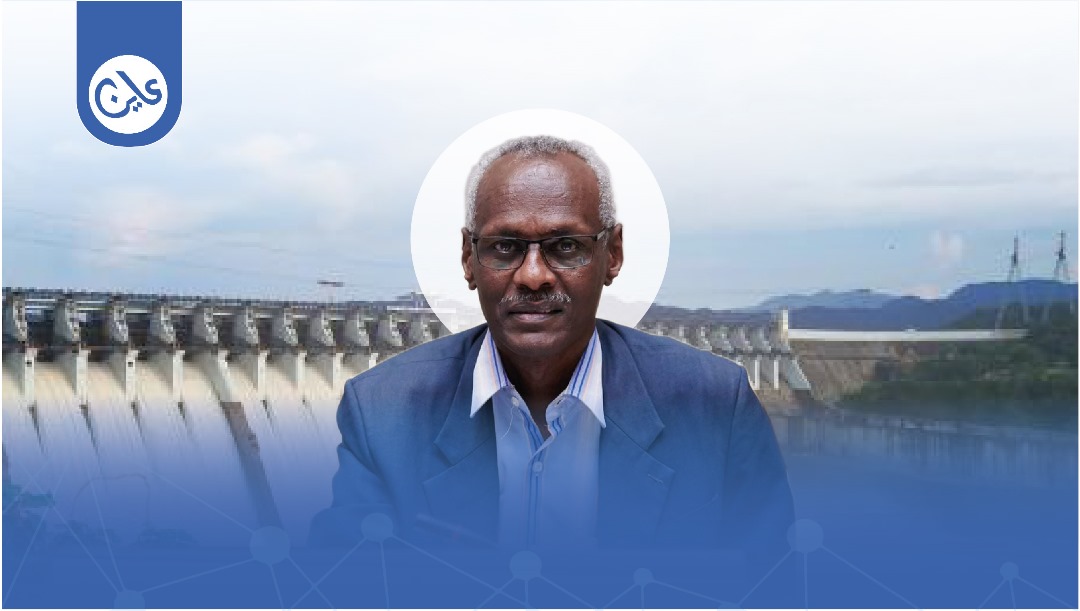

The risks of the Renaissance Dam to Sudan: an interview with the former water minister

28 July 2025

As Ethiopia prepares to officially inaugurate the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile next September, concerns are growing in the two downstream countries, Sudan and Egypt, regarding its potential impact on water security. This is particularly true in Sudan, given the lack of technical coordination and data exchange between the GERD and the Roseires Dam, which is only 110 kilometres away.

In this exclusive interview with Ayin, former Minister of Irrigation and Water Resources Yasser Abbas, one of the most recognisable figures who managed the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) during the transitional government, reveals his technical and political vision for the project’s outcomes and the real risks facing Sudan.

* How do you read the announcement from Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed that the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam will open next September?

As a Sudanese citizen, the dam has become a reality without a legally binding agreement on filling and operation or even the exchange of information. This poses a direct threat to the Roseires Dam and thus to the population in the north, despite the expected benefits.

* How credible is Ethiopia’s pledge not to harm Egypt and Sudan in the absence of a binding legal agreement?

In the context of international relations, legal agreements governing relationships between states must be concluded, not verbal commitments. Sudan is concerned about harm due to the proximity of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and the Roseires Dam. Sudan was previously harmed in the first year of filling in 2020, when some drinking water stations in Khartoum were out of service for several days due to lack of notification of the storage at the time, despite the small amount of water stored (only about 4 billion cubic meters). Sudan implemented technical precautions (mitigation measures) following this incident to prevent surprises. Therefore, a binding legal agreement on filling and operation, or at least the exchange of information, is a prerequisite for establishing credibility.

* Is there still hope of reaching a binding legal agreement? Or is it too late?

It’s not too late. A legal agreement is the only way to preserve everyone’s rights, under international law, to benefit from the waters of the Blue Nile, a river shared by three countries. The legal principle states that there should be “equitable and reasonable utilisation without causing harm.”

Sudan believes that Ethiopia has the right to build the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam to utilise the waters of the Blue Nile and also believes in its right to protect its water security, represented by the safety and operation of the Roseires Dam.

An agreement maximises the expected benefits of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam for the three countries. However, failure to reach an agreement increases mistrust and negatively impacts relations between neighbouring countries in other areas that could have been a source of cooperation, stability, and mutual benefit among the people.

* What are the most prominent risks facing Sudan because of the Renaissance Dam?

Due to the short distance between the Renaissance Dam and the Roseires Dam (110 km), the lack of daily exchange of information about water quantities, as well as dam safety measures for the Renaissance Dam with the Roseires Dam, does not allow for the safe operation of the latter, and therefore it is not possible to anticipate any surprises, whether the water quantities are large or small.

As I mentioned, this happened in July 2020, when some drinking water stations in Al-Salha and Soba went out of service, despite the scarcity of water stored at the time. This could have been avoided had there been an exchange of information under a legal agreement—noting that the exchange of information does not diminish the benefits of the GERD for Ethiopia.

* Does the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam pose a threat to Sudanese national security? And how?

Yes, in the absence of a binding legal agreement for filling and operating, or at least for the exchange of information between the Renaissance and Roseires dams, the operation of the Roseires Dam is unsafe. Consequently, the threat is not limited to the Roseires Dam alone but extends to the entire population northward along the Blue Nile and the main Nile. This applies in both cases: whether large quantities of water lead to flooding or small quantities lead to thirst.

* What are the potential impacts on agricultural and pastoral communities in Blue Nile, Sennar, and Jazeera states?

Firstly, it is crucial to highlight that the Renaissance Dam provides Sudan with numerous benefits, provided they exchange information. These include regulating the flow of the Blue Nile, which would increase electricity generation in Roseires and Merowe and will help mitigate floods such as those of 1946, 1988, and 2020. Additionally, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam traps silt, thereby lowering the maintenance costs of irrigation canals in the Jazeera and Rahad projects.

On the negative side, cliff farming (spate irrigation) is affected, which could be converted to permanent irrigation if there is an agreement (or prior knowledge) regarding the annual operating rules of the GERD.

* How do you assess the soundness of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam’s design in the absence of joint studies with Sudan?

It is true that the three countries participated in modifying the GERD designs during the construction phase between 2011 and 2014, and this cooperation was commended in the Declaration of Principles signed in 2015. However, it is also true that the lack of an agreement on filling and operation, or at least on information exchange with the Roseires Dam, threatens the latter’s safety, not necessarily because of the potential collapse of the GERD, but rather due to the lack of operational information.

There are also environmental and social studies that were supposed to be completed within 15 months of the signing of the Declaration of Principles in 2015 but have not yet been completed. Completing these studies and implementing their recommendations is crucial.

* Are there government studies predicting the dam’s impact on the environment and groundwater in Sudan?

Of course, my answer is based on the information available up until 2021, and I have no knowledge of what happened after the military coup on October 25, 2021.

Yes, there have been studies that have addressed the various impacts of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on Sudan, including environmental impacts (albeit somewhat limited), as well as the dam’s effects on groundwater, electricity generation, irrigation water, flooding, siltation, and others.

These studies were conducted to inform the negotiating delegation, and the conclusion was that the dam’s overall benefits outweigh its negative impacts, provided an agreement is reached on filling and operation, or at least an agreement to exchange information with the Roseires Dam.

* Do you think Ethiopia will use water as a political pressure card on Sudan in the future?

Yes. Ambassador Dina Mufti, spokesperson for the Ethiopian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, previously stated in a television interview with Al Jazeera in 2021 that Ethiopia would not object to selling water to Sudan and Egypt if there was a surplus.

The failure to sign an agreement on filling and operating the dam, or even to exchange information with Sudan, reinforces mutual suspicions and casts a negative shadow on relations between the neighbouring countries.

* How do you assess the role of the African Union as a mediator? Has Sudan lost confidence in regional mediation mechanisms?

The African Union squandered a valuable opportunity to embody the principle of “African solutions to African problems” by failing to grant the African experts, whom it selected, an effective role as mediators in bringing the views of the three countries closer together. Instead, it limited their role to that of observers, without the authority to interfere in the negotiations.

Sudan’s 2020 proposal to grant these experts a facilitating role in the negotiations was rejected by Egypt and Ethiopia. The African Union was expected to exert some pressure to persuade them to accept the experts’ opinion, but it did not.

Therefore, in early 2021, Sudan proposed the formation of a quadripartite committee headed by the African Union, including the United Nations, the European Union, and the United States, but this proposal was also rejected by Ethiopia.

* How do you view US President Donald Trump’s former statements describing Washington’s funding of the Renaissance Dam as “stupid”?

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) has become a significant strategic asset not only for the three countries but also for the intersection of regional and international interests in the Nile Basin, the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa, and the Middle East. In other words, it has become a political project par excellence, rather than a technical or economic one.

* On another note, how do you view water security in Sudan after the outbreak of the April 15, 2023, war?

The war created a complex geopolitical reality, with multiple and diverse alliances between the Nile Basin countries and the parties to the conflict in Sudan.

But I believe—and I hope I am right—that Sudan will overcome this war and will return more stable and stronger. It is the only country qualified to play a major role in reaching agreements within the Nile Basin, given its geographical location between the upstream and downstream countries, if we consider it a midstream country.

It should also be emphasised that the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam does not pose a direct technical threat to Egypt, given its distance and the presence of the High Dam, which has a massive storage capacity (twice the capacity of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam), enabling it to absorb any future hydrological shocks.

What must be emphasised is that the Nile waters are sufficient to meet the needs of the peoples of the Nile Basin, provided there is cooperation, not conflict.

The only way to protect the people’s interests is mutual benefit, as the Nile Basin Initiative’s philosophy stated before political tensions ended it.