Hijacking Humanitarianism: How Khartoum’s new authorities are cracking down on grassroots relief efforts

19 June 2025

In early May, the Khartoum State army-controlled de facto government issued a sweeping order that placed all Emergency Response Rooms (ERR) under the supervision of the Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC), a body closely tied to Sudan’s Islamist networks.

Framed as an administrative measure, the directive effectively criminalises independent humanitarian work unless it is cleared by the state—a devastating blow to grassroots networks that formed in the chaos of the war, ERR members told Ayin.

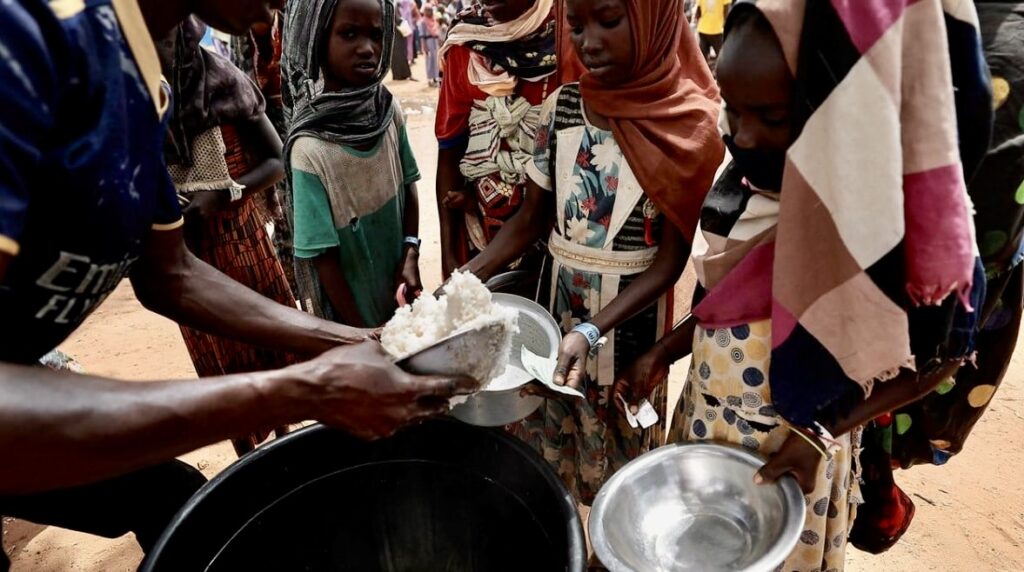

Across Sudan, ERR efforts—volunteer-led emergency kitchens, shelters, and medical support units—have helped communities survive in the absence of formal state services. Now, according to some ERR members, their very existence could be threatened. Community responders recounted having to decide between registering with a regime they oppose and risking arrest for carrying out their lifesaving work.

The UN has referred to the ongoing conflict in Sudan as contributing to one of the world’s worst humanitarian crisis with roughly 13 million displaced and over half the population facing acute food insecurity. In such a devastating context, state hostility towards volunteers supporting the war-affected appears preposterous, if not inhumane.

Opaque opposition

“In many observed contexts, the army-controlled government often oppose the ERRs, particularly when these groups operate independently or are perceived to be aligned with foreign donors or civil society networks,” says Asma*, an ERR volunteer.

Political analyst Mohamed Ibrahim states that the army-controlled government and the Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC) oppose the ERRs and any potential links to foreign backers, a stance that has long-term roots in the dictatorship of Omar al-Bashir. “The Humanitarian Aid Commission was not set up to support humanitarian efforts per se – but more to control those that do,” Ibrahim said. The former regime under Bashir expelled 13 foreign NGOs from Darfur after the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant against Bashir for crimes against humanity in Darfur.

“At the core of this animosity is control,” Asma added. “ERRs typically prioritise humanitarian principles and community needs over political interests, which can inadvertently expose the government’s failures or neglect. As such, ERRs are viewed not only as a threat to its authority but also as potential platforms for empowering communities beyond state control.

Politically, the army has always viewed the ERRs as their opponents, Ibrahim said. “Many of these volunteers are not neutral. They emerged as part of Sudan’s revolutionary civil resistance groups that have long operated independently of state control, particularly the Islamist-aligned elements that currently dominate state structures.”

“Unauthorised work”

Authorities claim the new oversight ensures aid accountability. But activists say it’s a ploy to dismantle the only functioning support systems left in the capital. “They’re not offering help—they’re eliminating those who are,” said Ahmed*, a Khartoum-based volunteer who asked not to be named for safety reasons. “It’s the same playbook from the Bashir era, only more ruthless.”

In May, several community kitchens in Khartoum were raided, ERR volunteers told Ayin. Equipment was confiscated and staff were detained. At least two emergency room volunteers in Omdurman were arrested on vague charges of “unauthorised work”.

Army authorities have targeted the ERRs since the conflict began in mid-April in 2023, Asma told Ayin. “In 2023, authorities forcibly closed an ERR in Gedarif, and it has not been re-established since. Elsewhere, in the Kordofan states, several ERR members were arrested by military intelligence, facing intimidation simply for trying to deliver aid and organise relief.”

The humanitarian space in Sudan has long been manipulated by political forces. But rarely has the divide between state-aligned aid and civilian-led relief been so stark. This time, the target is not foreign NGOs but rather Sudanese youths, who have stepped in where the state and major organisations have failed.

Rise of the ‘Dignity Committees’

The crackdown coincides with the recent emergence of a new structure: the so-called “Dignity Committees,” or “Lijan al-Karama”, formed under the auspices of the Khartoum state government and the Humanitarian Aid Commission.

Promoted as “local humanitarian coordination groups,” these committees are often stacked with individuals tied to former regime networks or Islamic charities long linked to the National Congress Party (NCP), local aid volunteers said.

“I believe they are a revival of the ‘Popular Committees’ that operated under the Bashir regime up until 2019,” Asma said. “These committees also appear to have a clear political character, as they are ideologically aligned with political Islam.”

“Before, we worked in public spaces. Now we work in whispers. But the needs haven’t vanished—if anything, they’ve grown.”

–ERR Volunteer in central Khartoum

In press statements, Khartoum’s HAC commissioner insisted the Dignity Committees are “neutral” entities created to organise relief fairly across areas under SAF control.

But volunteer groups say they are a front—an attempt to co-opt the community-driven model of the resistance committees and rebrand it under Islamist and SAF oversight. “They’re copying our structure, our language, even our slogans,” said a former resistance committee member in Bahri. “But their purpose is control, not service.”

Many Dignity Committees have been launched without any community consultation. In several neighbourhoods, they displaced functioning grassroots teams that had been operating kitchens and emergency shelters since early in the war.

In the Mayo neighbourhood in southern Khartoum, volunteers reported being summoned to a mandatory “registration session” led by HAC representatives and Dignity Committee heads. Refusal to attend was considered noncompliance. “They said we had to hand over our volunteer rosters, our food supply lists, even our donor contacts,” said a Mayo-based organiser. “It was surveillance disguised as cooperation.”

Some ERR members support the army’s initiative to support the war-affected but reject the idea of competition among them. “The needs here in Omdurman are huge; we need all the help we can get,” says one medical volunteer in Khartoum’s sister city. “But this does not mean we have to compete with one another – if anything, these new initiatives should work with us.”

Resistance in the shadows

Despite the risks, many ERRs continue to operate—underground, dispersed, and wary. What began as open coordination hubs have now transformed into covert cells. “Before, we worked in public spaces. Now we work in whispers,” said a central Khartoum volunteer. “But the needs haven’t vanished—if anything, they’ve grown.”

Mobile kitchens now shift location frequently. Volunteers avoid phones. Medical referrals are made quietly, often through encrypted apps. In some areas, ERRs have merged with newly formed local initiatives to keep service going while reducing exposure to surveillance.

But resources are dwindling as bank transfers are blocked and warehouses are being raided, local volunteers said. Aid that once came from diaspora donations or personal networks now struggles to reach the ground. An activist recounted how a checkpoint intercepted a shipment of medical supplies from Port Sudan due to its lack of “HAC authorisation”. It never arrived.

A veneer of legitimacy

Many fear the incident is only the beginning of a broader assault on civil resistance structures under the guise of humanitarian coordination. “What’s happening now is a replica of the former regime model,” said a civil society coordinator. “Embed your loyalists in local aid efforts, criminalise the rest, and dominate the narrative.” Already, some Dignity Committees coordinate directly with SAF units, distributing goods. These moments are filmed, shared, and weaponised for legitimacy.

Fathi Sabah Al-Khair, a Resistance Committee activist from Karari, Omdurman, argues the Dignity Committees act as a cover for the Islamist forces. “Their real aim is to conceal the widespread violence and crimes committed by Islamist groups fighting alongside the army, particularly the Al-Baraa Bin Malik Battalion, under the guise of providing aid.”

The strategy is working. Foreign actors in Port Sudan and beyond now engage with the Dignity Committees under the assumption they are grassroots structures—unaware of the manipulation underneath, local sources told Ayin.

In a city of hunger and fear, silence has become both shield and weapon. And yet, behind every shuttered kitchen and disbanded aid room, the will to resist endures. “It’s what we defend, even if we must do it in silence,” one volunteer said.

* Names changed to protect the source’s identity