Darfur: UNAMID to leave amid insecurity as cyclical violence continues

21 December 2020

“Protection of the displaced cannot be entrusted to those who killed them!” shouted one protest leader at the beginning of the second week of protests at Kalma camp, South Darfur State. Thousands of displaced residents at Kalma continue their sit-in demanding that the hybrid peacekeeping mission of the African Union and United Nations in Darfur (UNAMID) remains.

But the United Nations (UN) and the African Union (AU) already decided nearly two months ago that UNAMID would exit Sudan by the end of this year. Instead, the paramilitary militia, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and other national security forces will ostensibly pick up UNAMID’s mantle to protect Darfur citizens.

“This is madness,” says Osman Adam, a resident of Kalma Camp who was forcefully displaced by armed gunmen he claims have links to the RSF several years ago. “The same people who kill us, take our land, the same people who have forced us to live here –are now going to protect us?”

The Coordinator for Displaced and Refugees in Kalma Camp, Yaqoub Muhammad Adam, told Ayin they would instigate larger protests involving all 175-displacement camps in Darfur if their security concerns are not heard.

Formerly known as the ‘Janjaweed’, the RSF were prior supporters of ousted dictator Omar al-Bashir and are widely believed to be the culprits behind atrocities in the Darfur region and beyond.

In early September, a joint UN-AU report claimed 392 female-headed households were displaced from the Sortony Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp in North Darfur after an RSF commander accused some of them of being allied to the rebel Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) under Abdel Wahid. Some of the women reported physical assaults by members of the Forces.

Some of those residing in Kalma Camp have remained displaced since the conflict erupted between rebel groups and the former government in 2003. Despite nearly 17 years in passing, insecurity and displacement persists in Darfur and often follows a forlorn pattern. Smaller conflicts –sometimes purposefully instigated — ensue between two communities that then act as a precursor to a greater, armed conflict. The net result is those with fewer arms are displaced and their land is appropriated.

A cycle of violence, land seizures

“Most of these crimes against civilians [in Darfur] start with conflict between two persons,” says Ahmed Gouja, Regional Director of the Darfur Network for Monitoring and Documentation, a local human rights body that tries to keep track of the myriad of human rights abuses in the region. “Armed tribal groups always seize fertile lands by force of arms. When the original owners of the land return, they are assaulted, deprived of their land and expelled by force.”

Given this repeated scenario, the opportunity for the displaced to return to their land is near impossible.

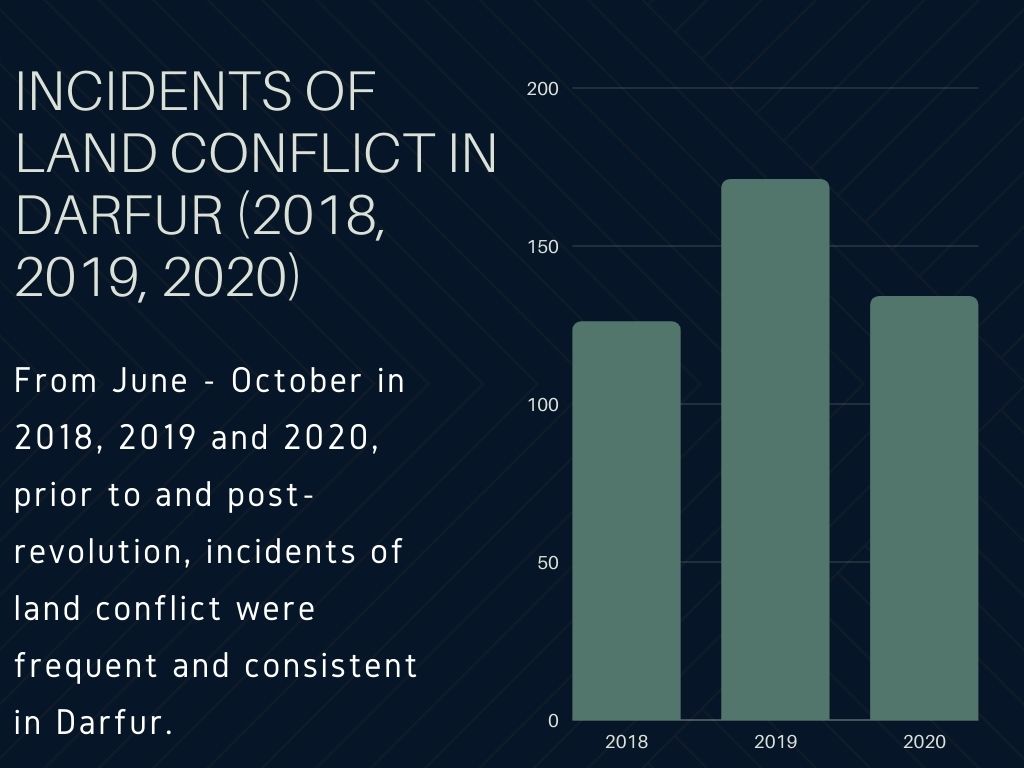

Land related conflict, predominantly involving crop destruction by pastoralists, remained almost constant in 2020, the AU-UN report said, with 134 incidents between June and October this year.

Struggling with population growth, climate change, displacement and urbanisation, pastoralists in Darfur have changed their ecological needs –especially their need for access to water and grazing land, the AU-UN report said. In some cases, this had led armed pastoralist groups to forcefully resettle in places of origin of internally displaced populations.

Gereda

One area listed by the AU-UN report where land-related conflict has been hit hardest in Darfur is Gereda town in South Darfur. Inter-communal conflicts between the Fallata pastoralists and the predominantly farming Masalit community has taken place twice in July and October this year alone, displacing hundreds and killing dozens of people.

According to the mayor of Gereda town, Haroun Omar Aydam, around 50-armed Fallata pastoralists on camels and horseback attacked the area killing at least 14 civilians and burnt down 200 homes. The attack seemed like a repeated offensive that they witnessed less than four months earlier. The Fallata were meant to stay away from Gereda until a reconciliation conference took place between the Fallata and Masalit communities, according to Gereda resident Adil Ali Yacoub. But the head of the RSF in Gereda and South Darfur State, Brigadier Abdel Rahman Gomaa Barakat, ignored this directive, Yacoub said, allowing the Fallata to enter the town where the dispute occurred between the two communities.

“Those people were Janjaweed, just like before, like they did in the past,” said Zainab Khamis, a survivor of the October attack. “When they came here they took our donkeys and burned everything and left us with nothing. No one has anything but the clothes they were wearing, some of us don’t even have shoes.” With the current imbalance of arms in the hands of pastoralists, says Musa Ali Shumo, there is no chance for peace to be restored where the displaced can return home. “If you want people to return to their lands whilst there is no sustainable peace and security, it will not work, there are people who have sticks and people who have Kalashnikovs.”

While many of the displaced residing in Gereda are supportive of the peace process, they are also aware that Darfur has a long way to go prior to achieving peace. “Yes, a peace agreement was signed and we support the peace process but peace is yet to be complete,” Ali told Ayin. “If all the armed movements do not sign the peace agreement, we don’t think this current peace agreement will fulfil the people’s demands.”

Nowhere is this perhaps more evident than in the Jebel Marra area, Central Darfur, where reports of in-fighting between factions of the rebel Sudan Liberation Movement / Army have flared up since late September. UNAMID estimates around 27,000 people are now displaced due to the on-going conflict that largely focuses on the control of gold mines in the region. But Sudan Liberation Movement Political Spokesman Muhammad Abdel Rahman denies the existence of a widespread conflict in Jebel Marra, claiming they have dealt with a small splinter faction that allied itself to government security forces, including the Rapid Support Forces.

Whoever the original culprit may be to the violence Sudanese citizens are experiencing in the Jebal Marra area, the fact persists: the Darfur region remains insecure and cyclical violence is set to continue.

During a November 2019 visit to Darfur, Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok pledged to ‘voluntarily repatriate displaced people and refugees’ after speaking to leaders within the IDP camps who presented their demand, including security in the region. A year later, few residents of Gereda harbour any confidence in this promise.

“We want our government to have the courage to face this crisis, if they do not address it, it’s guaranteed that what is happening now is going to continue in the same manner and the killing will spread to other areas, the numbers of the dead will increase, there will be more widows, more orphans and there will be more people displaced,” said Gereda resident El Tayib Adam. As long as people in Darfur believe in the gun as the solution to all their problems, Darfur’s restive trends will continue, Adam says. “If someone is wired to the mindset that if you kill people and take their land – this land then belongs to you –then there is nothing to stop them.”