The Comeback of Sudanese Cinema

16 February 2021

“The new wave of Sudanese Cinema” is how Mohamed Kordofani, a Sudanese Filmmaker described the current rise in Sudanese filmmaking following the revolution and ousting of three decades of censorship of the arts under the former National Congress Party regime.

New films produced in the latest years carry hopes of the youth to one day have a thriving movies industry in Sudan. Several of those films received global recognition and won awards internationally and locally at cinematic events.

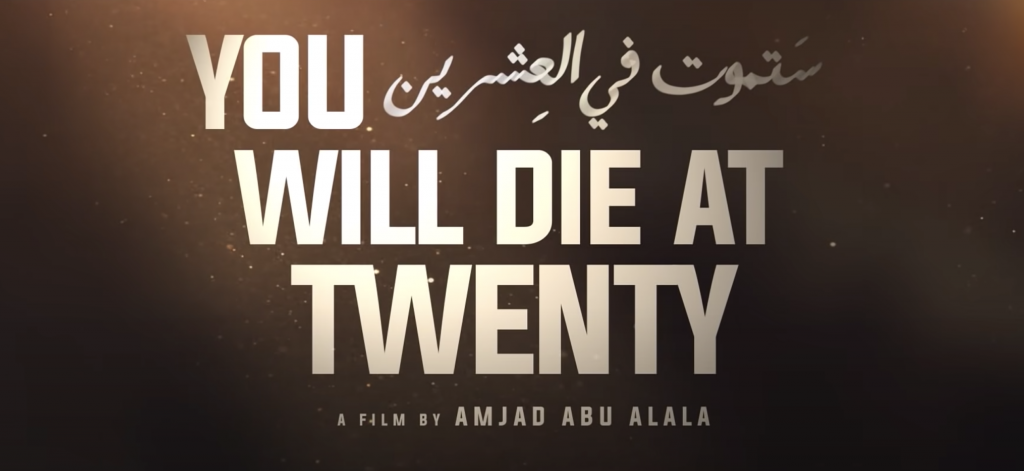

“Khartoum Offside”, “Talking about Trees”, “Beats of the Antonov”, and the well-known “You Will Die at Twenty” are some of the new cinematic productions that spark hope of a filmmaking revival in Sudan.

Glamorous Past

Sudan was pioneering in filmmaking in Africa around its independence with Gadallah Gubara producing the first African coloured film in 1955, “The Song of Khartoum”, followed by many films he and others made of what later was known as Khartoum’s golden era for cinema.

The film industry back then was developing, and the culture of cinema was thriving in Khartoum as people made a habit of going out to watch all sorts of films in several open movie theatres in the capital and other states during the sixties and up to the eighties.

In 1989, the National Congress Party (NCP) under former president Omar al-Bashir seized power through a military coup that reverted this trend. The film industry was ostensibly censored and suppressed –labelled “un-Islamic”—and cinemas were either destroyed or converted across the country.

The national institution of cinema “Sudan Film Unit” was dissolved in 1991, fiscally suffocated into oblivion.

National Congress Party vs. Film

But even during this oppressive period, small personal initiatives were taken to revive the film industry and the cinema culture within the country. Filmmakers produced small independent pieces, many groups developed events to raise awareness and encourage the cinematic arts through festivals, among other efforts.

Most of the projects were limited to short features that were premiered in festivals abroad, rarely showcased inside the country. Bodies like the Sudanese Film Group, an independent cultural platform, and other initiatives to revive the beleaguered industry.

“Bashir’s era was a time of oppression, centralisation, Arabisation and Islamisation as well,” says Talal Afifi, a filmmaker, actor and head of Sudan Film Factory. In addition to creating films, Afifi supports various cultural events such as the Sudan Independent Film Festival, a week-long annual event promoting independent cinema.

“We are not a political body of course – with a limited budget – but in our workshops and activities, we are very sensitive towards inclusive representation. We try to go outside the capital as well and work in other cities to raise awareness and capacity of cinema and filmmaking”, he told Ayin.

Attempts of revival

Mohamed Kordofani, who directed “The Kejer’s Prison”, and “Nyerkuk” in the recent years, remembers well the challenges they faced making films under the former regime, often filming in secret. “We couldn’t get permits and papers, and that goes for showcasing as well; with the risk of being subpoenaed anytime.”

“My first film was a short feature named “Gone for Gold” in 2014, and it was about two local gold miners in northern Sudan. Filmmaking came gradually for me as I wrote short stories since I was in college, then learned photography followed by film-editing,” he says.

“Gone for Gold” was premiered at the Carthage film festival where it won an award for best Arabic short film followed by many awards in other international, regional, and local festivals. This, he says, represented his entrance into the independent film industry.

Like Kordofany, other aspiring filmmakers have recently produced award-winning films. One film in particular, “You Will Die at Twenty” was celebrated widely as Sudan’s seventh feature-length film made in Sudan after more than two decades.

The film received a variety of responses inside the country –from those who deemed its language inappropriate in parts to others who celebrated its presence as a bold new young voice for Sudan. Unfortunately, it was not screened in its homeland despite being featured via other international platforms.

Afifi says that censorship was not the issue; “I’m in charge of the distribution of it and the authorities gave us the green light to screen, but we had technical and other logistic challenges to screen it here; and then came the lockdown,” he explains, adding that most of the people speaking negatively about it did not see it yet. “But this feedback isn’t strange considering our society, but I think that people will change their minds.”

However, the film was fairly highlighted by media, praised by critics, and won many awards, in addition to being submitted as Sudan’s first entry to the Oscar awards under the International Feature Film Category. Unfortunately, it did not make it to the shortlist, but it certainly made Sudanese film history.

Post Revolution

Post Revolution

“There is more support not just acceptance now,” Kordofani says. Accessing permits to film and approval for screenings is far easier, he adds. Another committee set up to revive cinema in Sudan was formed that now submits recommendations to the ministry of culture. “They [the ministry] nominated “You Will Die at Twenty” for the Oscars, this could not have happened during Bashir’s era.”

But total freedom and acceptance of film in Sudan –not simply from authorities but also the public—will take time, Afifi says. “We are trying to get our input in this post-revolution period and hold workshops to develop cultural policies, and we are trying to assist the government in this regard.”

“Working on enlightenment is a process, and it’s social progress. We trust that people are always able to gain new values. This might take a couple of decades, but it is a process,” he added.

Future Aspirations

“Our aim is to avoid being fund seekers –we want to be contributors and to pay taxes – through production and selling tickets and make the Sudanese film industry a thriving enterprise,” Afifi said.

Kordofani agrees that having a productive, independent, and successful film industry in Sudan is the hope of any filmmaker but thinks this might not happen in the near future.

“After recent well-known films such as “You Will Die at Twenty”, “Talking about Trees”, “Khartoum Offside” and others; there has been more interest towards Sudanese cinema,” Kordofani says. “However, this interest has yet to be translated into investment in the industry.”

Kordofani also thinks that for a successful comeback, people need to have a modern approach and a creative way of thinking that works for all. “People have nostalgia for Sudan’s past cinema, but we need to both revive the culture of cinema in Sudan as well as keep up with the modern industry that satisfies different tastes by being present in all platforms.”

“You Will Die at Twenty” is now streaming via Netflix platforms.