Running out of time – the dire need for food aid to reach Sudan’s warzones

27 November 2023

Al-Shifa Adam Hamad has found herself single-handedly supporting nine children while conflict displaced in the Adré refugee camp in Chad. Five of these children are her own, from her husband who has been missing since the outbreak of war, and four children from her sister who was killed in her home while in West Darfur’s capital, Geneina.

Every month, Al-Shifa receives small quantities of corn, cowpeas, cooking oil, and lentils. Adam told Ayin she resorts to doing whatever work is available to her so that she can cover her needs with the nine young children. “It is true that aid is provided to us, but it is not enough for a full month.”

While the support is limited, the refugee camp in Adré marks one of the few locations where the war displaced from Darfur can receive humanitarian aid, says Adam Rijal, the official spokesman for the displaced in Darfur. “The humanitarian situation in the Darfur region, especially in the displacement and refugee camps, has reached a dangerous stage, the situation has become catastrophic,” Rijal said in a statement last week. “The displaced people in the camps who were relying on the World Food Program to disburse food rations have reached seven months and no food has been provided to them. There is no work, however marginal, to help the displaced meet their needs, food scarcity of basic items has induced prices to soar in the market –not to mention the failure of the agricultural season.”

The war that broke out in mid-April this year in Sudan on 15 April between the army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) put more than 20.3 million people, or 42 percent of the country’s population, at extreme levels of food insecurity. According to the World Food Program (WFP), this is particularly acute for over six million people stuck in conflict areas in the Sudanese capital, North and South Kordofan states, and the entire Darfur region.

Humanitarian access

On 9 November, the army and the RSF signed, after tremendous pressure exerted by the American, Saudi, and African facilitators, the humanitarian track agreement, allowing humanitarian organizations and United Nations agencies to work in the contested areas in Sudan.

According to proposals put forward by the United Nations, the process includes identifying safe corridors in conflict areas such as the Darfur region, Kordofan states, and the Sudanese capital, and stopping armed clashes between the two warring parties during the distribution operations, which are determined by hours and dates according to the facilitators’ communication with them.

“The humanitarian track agreement signed between the army and the Rapid Support in the Jeddah platform will prioritize protecting civilians and reaching them, and the need for the two conflicting parties to provide strong guarantees to implement the operation,” says Clementine Nkweta, the UN Humanitarian Coordinator in Sudan.

Tenuous security

One United Nations official –who is not authorised to speak to the press and requested anonymity —believes the Jeddah proposal is a good first step, but certainly not a complete solution to the humanitarian access challenge. Ensuring the safety of relief workers distributing aid in the conflict zone is far from guaranteed, the official said. At least 19 aid workers have been killed in Sudan since the conflict erupted seven months ago.

Given the disparate forces loosely aligned to the RSF, aid workers have expressed their concerns about the level of commitment to implement the humanitarian agreement on the ground.

The former advisor to an international organization that worked in Darfur, Ali Haj Abdel Rahman, told Ayin that even if a specific area of Darfur is designated to receive humanitarian aid, there are few guarantees that the aid will reach its proscribed target.

Ali Hajj believes that the main problem with humanitarian aid is not only safe passage but also the lack of genuine will on the part of the warring parties. “They are fighting relentlessly over the heads of civilians, often using the public as human shields…they certainly do not care about distributing humanitarian aid,” Ali Hajj said. “Rather, there are no real guarantees that the warring parties will not confiscate the humanitarian aid by gunpoint.” These guns, he added, do not necessarily need to belong to the warring parties that have agreed on the humanitarian ceasefire.

Armed gangs with little or no direct connection to the warring parties have emerged in the conflict areas as a direct result of the widespread access to arms and increasing competition over limited resources, says journalist Issa Dafallah. Dafallah has reported firsthand on cases where attempts to deliver humanitarian aid have failed due to armed gunmen that may not necessarily be linked to either the RSF or the army. “A humanitarian convoy consisting of 17 trucks left Port Sudan last September and arrived in the Darfur region. It was reduced to 10 shipments,” Daffallah said. “Looting gangs confiscated seven trucks on the road in North Kordofan.”

Running out of time

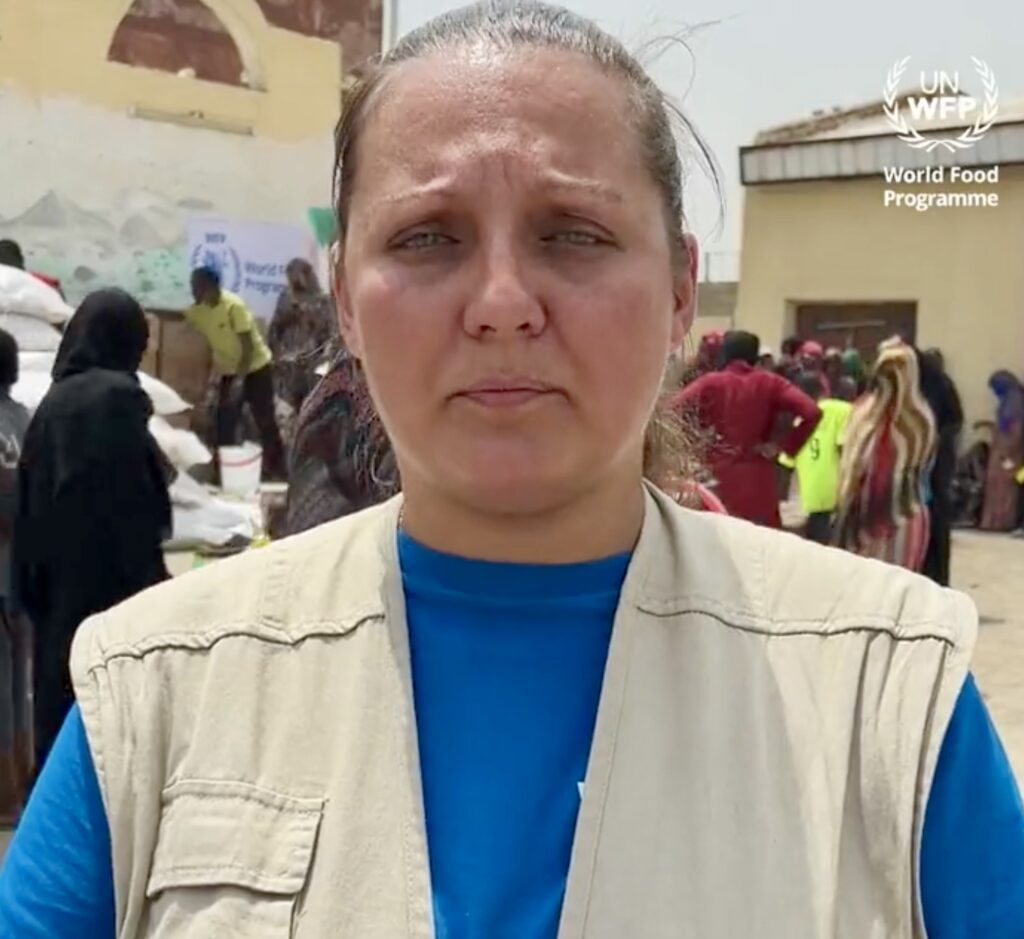

Despite these challenges, many aid workers are determined to see this agreement be pushed through given the dire humanitarian situation on the ground. “There are around 6.3 million people who are in emergency levels of hunger –that’s one step away from famine,” says WFP Sudan’s Head of Communications, Leni Kinzli. “Almost 70% of them are in areas we are not able to access.” Kinzli told Ayin that the WFP is cognizant of the fact the humanitarian access commitment made in the Jeddah talks may take time to materialize. But time is running out. Civilians most affected by the war are also those who face the highest levels of food insecurity and remain the hardest areas for humanitarian actors to reach, Kinzli added.