Graft in aid distributions, amidst Sudan’s famine

13 April 2025

Humanitarian aid to Sudan, facing the worst famine in modern history, has remained limited due to limited access and funding. What little aid does reach the Sudanese populace may actually be even less than aid agency estimates due to graft in local aid distributions.

The humanitarian research organisation Ground Truth Solutions has conducted a survey in the states of Al-Gedaref and South Darfur to assess the effectiveness and challenges of humanitarian aid delivery. The survey provides an in-depth analysis of the obstacles hindering aid distribution and the overall impact of humanitarian efforts in these conflict-affected regions.

Al-Gedaref

The eastern Al-Gedaref state, an agricultural hub bordering Ethiopia, has become a host to a plethora of conflict-displaced people. The sharp rise in internally displaced people (IDPs) in Al-Gedaref has placed immense pressure on the state’s already fragile infrastructure. A survey was carried out in September 2024 across the state of Gedaref, engaging over 400 participants from various communities. Those surveyed identified illness as their primary concern, yet access to medical care remains severely limited due to high costs and a shortage of operational facilities.

It is little wonder disease has spread in the overcrowded shelters for the conflict displaced, with cases of malaria, dengue fever, and cholera common among them. An influx of people fleeing repeated attacks by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Al-Jazeera State has led to overcrowding, straining resources and exacerbating an already overburdened system.

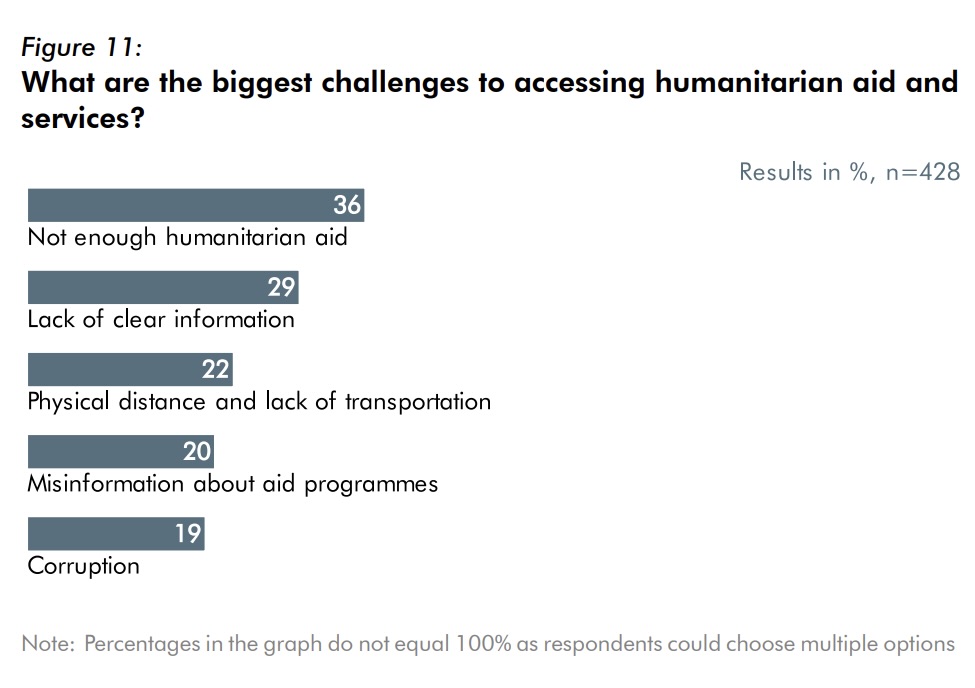

Despite Gedaref having better humanitarian access than other parts of Sudan, aid remains insufficient, with only one-third of people receiving assistance in the past six months. Over half of those surveyed, 55%, claimed accessing humanitarian aid was extremely difficult. While more than a third of those surveyed (36%) cited a lack of humanitarian aid as the primary access challenge, others referred to poor information, misinformation, long distances to aid centres, and corruption.

Around 15% of those surveyed identified corruption as their greatest obstacle to receiving aid. “Aid only goes to certain people, like those in charge of distribution and their acquaintances and relatives. It’s not distributed to all people,” said a displaced woman in Ar Rahad.

“The real registration happens in secret, while the false registration is in public,” said one displaced man living with the host community in Ar Rahad. “Distribution is based on connections and favouritism. When we ask why we weren’t given anything despite our names being registered, they say the names were missed or not approved. Meanwhile, we see the relatives of those in charge receiving aid, even getting extra.

Humanitarian operations in the state face significant bureaucratic and logistical challenges, despite support from international aid agencies, according to Ahmed Awad, a member of the voluntary Emergency Response Rooms who assists the conflict-displaced in Gedaref. “Security agencies stand in the way of organisations delivering aid and require special permits to distribute humanitarian assistance,” he said. Awad also highlighted cases of mismanagement and poor oversight by aid agencies in their aid distributions. As an example, he pointed to the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), which allocated 10 million Sudanese Pounds (roughly US$4,000) through the coordination of initiatives with the state ministry of youth and sports in Gedaref. However, the allocated time frame of six days was insufficient, leading to rushed distributions and funds being spent on non-priority areas.

The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), however, refutes this claim. “Our approach is rooted in genuine community engagement,” said Mathilde Vu, NRC spokesperson to Ayin. “We work hand in hand with local communities to set clear and fair criteria for selecting who receives aid. This method ensures that support reaches the most vulnerable and that the process reflects local priorities. We also involve communities in identifying beneficiaries. Our team then conducts thorough verification to ensure fairness and minimise errors.”

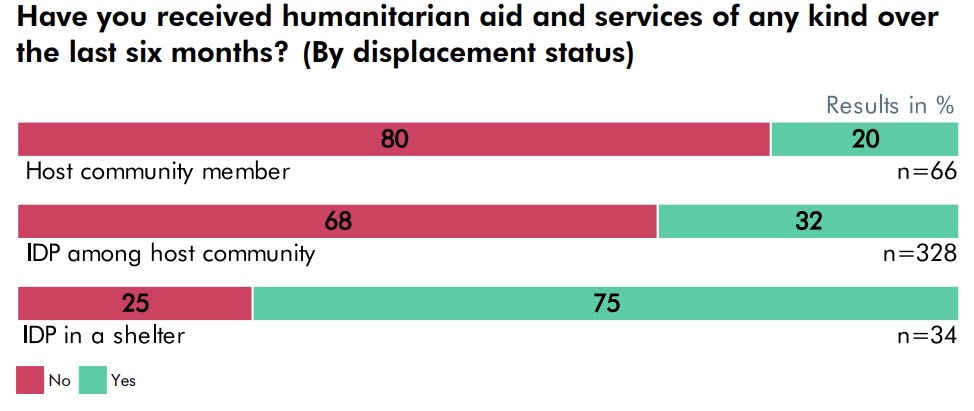

Host community members and those displaced outside shelters are less likely to receive aid than those in shelters, as aid providers must make tough choices due to resource constraints. Over the past six months, 80% of host community members have not received any humanitarian aid or services, while 68% of internally displaced persons (IDPs) within the host community have also gone without assistance.

“Aid is only given to people living in the schools (used as informal displacement shelters) and not to those living in the community,” a displaced woman living among the host community in Madeinet, Gedaref, stated.

A displaced woman living among the host community in Ar Rahad described her frustration: “When we hear that aid has arrived, we go because we are registered. We stand in line, and they call the people they know, and we are told that our names are dropped. We leave empty-handed.”

South Darfur

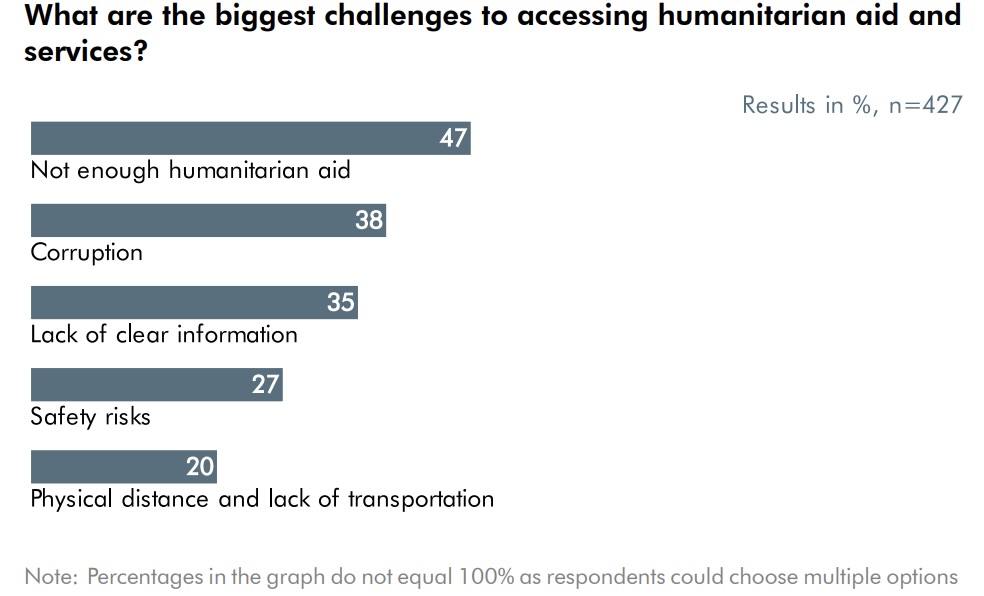

A similar survey by Ground Truth Solutions, involving over 400 people across South Darfur State, indicates challenges similar to those in Gedaref, where a lack of transparency in aid distribution has fuelled widespread suspicions of misconduct and favouritism.

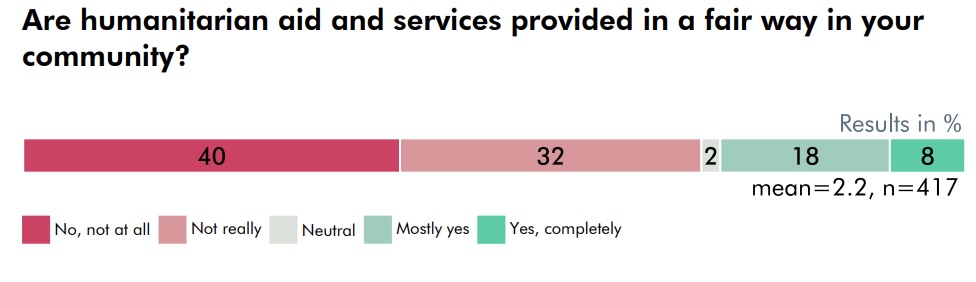

Seventy percent of the respondents stated they are unaware of the mechanism used by humanitarian aid providers to determine distribution methods.

“The aid is distributed to people who don’t need it, while those who truly need it are sitting around and have no idea what’s happening,” a displaced woman living in Kas explained. “They don’t know who to talk to or complain to. Honestly, there is no fairness in the distribution.”

Similarly, a displaced woman in Buram also questions the nature of aid distribution. “I don’t know the exact reason, but occasionally they give aid to people who don’t need it, like someone healthy and capable of working, while they neglect someone who is ill or disabled and unable to work.”

Only 8% of those surveyed in South Darfur believe that humanitarian aid and service providers distribute assistance fairly within their community. Alarmingly, the second most commonly mentioned barrier to aid access for the displaced is graft.

“Aid isn’t distributed at all; instead, it is excessively hoarded in the homes of local leaders, and the eligible individuals and the poor receive nothing,” a displaced woman living in one of the shelters south of the capital city, Nyala, said. “Discrimination based on tribe, familiarity, or where you live is the greatest injustice we face in this centre, and all the funding comes from the supervisors.”

According to one man based in the same camp, while sometimes distributions are done well, at others, local leaders such as the camp’s sheikhs misdirect the aid. “They are the root of the corruption,” he said.

While 45% of those surveyed in South Darfur State reported receiving some form of assistance in the past six months, higher than those interviewed in Gedaref, they also say aid distribution remains deeply uneven. Those internally displaced living among host communities or in makeshift shelters are significantly less likely to receive support compared to those within displacement camps. The situation is particularly concerning for those in informal shelters, which often lack even the most basic services.

“We walk through the open fields to get straw and build with it,” one displaced woman in Buram said. “There were multiple times when we found ourselves spending the whole rainy season sleeping inside a hut that had water leaking through it.”

The findings from South Darfur and Gedaref echo challenges observed in other parts of Sudan and underscore a harrowing trend of unequal aid distributions and deepening mistrust. The lack of transparency, combined with insecurity and access restrictions, continues to hinder effective humanitarian response to displaced populations, especially those in informal shelters or living within host communities.

“These gaps deepen people’s vulnerability and trust issues. We need fair, transparent aid that truly reaches those who need it most,” said Awad.