“Companies leave our land! Health before everything!” shouted demonstrators last week in Kalogi, South Kordofan State. Civilians are in protest over the on-going presence of gold mine companies whose widespread use of cyanide in their gold extraction process continues to detrimentally affect the environment, local citizens told Ayin.

The protests and clashes have been so strong, Sudan’s Council of Ministers issued directives on Wednesday to halt all use of toxic mercury and cyanide in mining operations across the country. The Council also ordered amendments to the operation agreements of mining companies, calling on these companies to aportion a percentage of their profits for local development projects.

Frustrated by years of inaction, local citizens took to targeting mining companies last week, setting fire to five separate companies, only to be targeted by security forces affiliated to these companies this week.

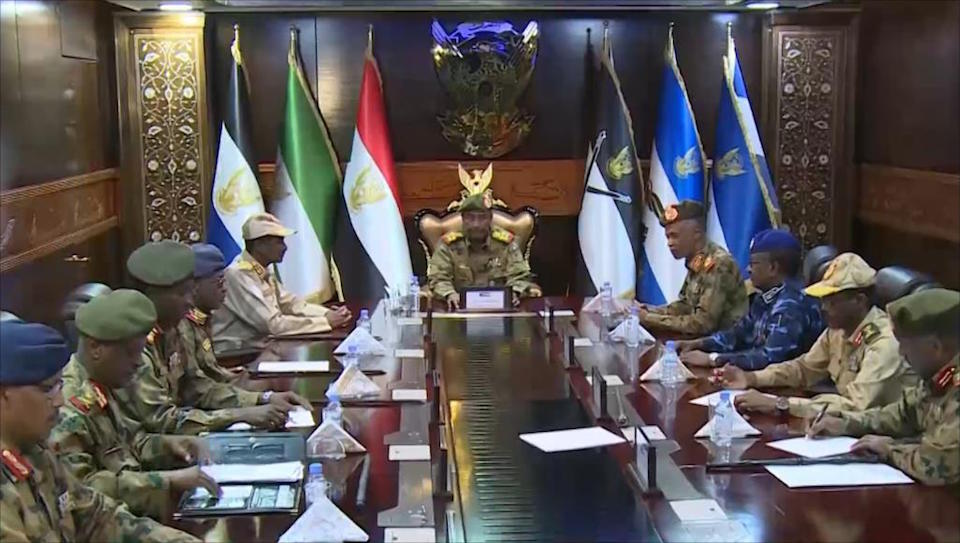

On Monday, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia, led by Sovereign Council member Lt. Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Daglo (aka “Himmedti”), attacked protestors living near goldmine operations in Talodi, South Kordofan State. An estimated 27 vehicles from the gold-rich state’s capital, Kadugli, descended upon residents living near the Tolodi gold mines, detaining 14 people and looting items, according to a statement by the Human Rights and Development Organisation (HUDO).

Sudan is the third-largest gold producer in Africa, following South Africa and Ghana, and South Kordofan State represents the epicentre of both traditional and commercialised mining for the country. But according to local citizens, this has not enriched them over the years –instead, poor mining practices have poisoned the ground, affecting child births and killing animals and plants across the state. After mining companies ignored an order by acting State Governor Major-General Rashad Abdelhameed to close all mining plants on September 11, civilians took to targeting the companies directly.

Factories burnt

On 3 October, local citizens launched a mass protest in Talodi town, burning the El Ein El Zarga (“Blue Eye”) and the International Company (formerly known as “Al Sunut”) gold-mining plants as well as the offices of two other companies – Al Junaid and Abersi, according to local citizens and a statement by the Sovereign Council. “We have protested for a long time and the governor did nothing so we decided there was no alternative but to attack the companies and dismantle the machines,” said local resident Musa Salah. Citizens also attacked an RSF base where these militiamen support the provision of machinery and other equipment for the mining companies.

RSF forces at Junaid and other security forces at the International Company fired at the protestors, injuring nine people, according to Sharuf Al Deen Fadul, one of the injured protestors and member of the opposition umbrella group, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC). Fadul told Ayin at his hospital bed in the capital’s twin city Omdurman that one of those injured had to have his leg amputated. “It took two days to come here [Omdurman] from Talodi due to bad roads,” Fadul added. “If the roads were better or there was a decent hospital along the way we could have saved his leg. These gold mining companies just steal gold, they cannot even be bothered to build a road to help transport their loot.”

Local citizens of Kalogi provided authorities guidelines on how to extract gold safely from the area but these provisions were ignored, says Kalogi businessman Adil Ibrahim. “There are many companies using cyanide and yet we do not see any development, not even a road despite the fact you could build a road of gold here,” Ibrahim said.

Activism against the gold mines is nothing new in South Korfofan. Talodi-based activist Mohamed Mustafa told Ayin they set fire to the Sunut Plant (now called “the International Company”) back in 2012. “We need to stop these companies and take everyone who helped these companies to build here to court. Let us focus on agriculture, instead of poisoning ourselves.”

Countrywide protests

Protests against the use of using unsafe gold mining procedures have not only taken place in South Kordofan but across the country. In South Darfur, the government announced the suspension of mining activities in Mershing, East Jebbel Marra and El Wehda localities this week in reaction to concerns over the toxic dumping, according to news reports. For the past two weeks, residents of Sawarda, Northern State, have protested against the International Company (the same entity operating in South Korfofan State), according to Hazem Sherif, a member of the National Committee for the residents of Sawardah. Sherif says they have held a rally outside the factory, based just kilometres away from a residential area, forcing staff and vehicles to leave. But large tanks and storage barrels of cyanide remains on the premises, he said.

Ad-hoc hazards

Authorities focused on gold after South Sudan gained independence in 2011, cutting the country off from 75 percent of its former oil supplies. “From that point, Sudan switched to mining but without any research or planning, no environmental or economic studies conducted,” said Sadiq Tawar to Ayin last year, as a former Environmental Science Lecturer at Nelein University in Khartoum. Tawar is now a member of the transitional government’s Sovereign Council. Civilians were allowed to mine without instruction without supervision or guidance, Tawar said. “Authorities would only set up a small tent near where people mined to collect revenue.”

With such an ad-hoc setup, hazardous conditions for miners and the communities living around these mines were inevitable, Tawar added. “In Sudan, the company comes, makes an agreement with the government in Khartoum without speaking to the people in the mining area. They give the local government money and then they just start extracting.” Due to corruption, mining companies could set up anywhere despite the fact such operations should be done far from residential areas. Once local residents protest these mining activities, the government reacts with force. “All these companies were built by force.”

The highly toxic industrial wastes that have triggered years of protests against the mining operations stems from the “karta” process. Soil and stones are milled and treated with mercury to extract around 30 percent of gold in the rocks, according to a 2018 report by the human rights organisation, Sudan Democracy First Group. The leftover soil is then treated with cyanide to extract the remaining gold. The waste soil, known as “karta”, is then dumped into the earth leading to heavy pollution with long-term consequences.

To extract one kilogram of gold needs around 50 kilograms of cyanide, according to Tawar. Each mining company is extracting thousands of kilos of gold. “Just imagine 50,000 kilograms of cyanide being dumped into the surrounding earth,” Tawar said. A lethal dose of cyanide is estimated at .2 milligrams.

Toxic life

The near eight-year dumping of toxic mining wastes has played a heavy toll on civilians and animal and plant life alike, local residents told Ayin. “We cannot live normally due to cyanide,” said Talodi-based protestor Zahra Talha. Miscarriages and infant deformities are prevalent in the residential areas near the mining operations, local citizens said. According to a doctor at Talodi Hospital who spoke to Ayin on condition of anonymity, there are around two birth defects for every 10 births delivered. Kashabha Nasredin, a Talodi resident, said his sister recently gave birth to a deformed child. “You cannot even see the difference between his eyes and his nose, there is no border,” a distraught Nasredin said. “As people from South Kordofan, we have two options in life. Either to die of war or die of mercury.”

Talodi is not the only area facing irregular births and miscarriages. “Most of these mining companies are affecting women the most, especially pregnant women,” Salah from Kalogi said. “There is something abnormal with all the babies born these days – in less than two weeks we have come across seven cases of infant deformity in Kalogi.” In August, the ‘Demanded Bodies Association’, a human rights monitoring group, recorded 1,500 cases of foetal and neonatal deformities in Sudan triggered by mining companies using harmful chemicals such as cyanide and mercury.

Animals and plant life are similarly affected across the state. Talodi-based veterinarian Ibrahim Bashir told Ayin livestock are dying from drinking infected water. In a week, around 7-12 cows and as many as 14 sheep can die, he said. While government fact-finding missions in the past never revealed any conclusive reports linking the mining waste to the harmful effects against the environment, many local studies prove a conclusive link to the toxic dumping and environmental degradation, Tawar said. Studies in Tadamon County in the Terter area, Tawar told Ayin, demonstrate the link between infant deformities, miscarriages and the misuse of cyanide for gold extraction.

Security owned

Despite evidence linking harmful gold mining practices to severe environmental consequences, the mining companies have enjoyed a certain level of immunity due to their affiliations to national security forces. According to local activists and members of the FFC, all of the gold mining companies operating in the Talodi area are either owned or co-owned by security forces aligned to former president Omar Al-Bashir. While Himmedti has shares in the Al Junaid mining company, former spy chief Salah Gosh is the suspected owner of the International Company and El Ein El Zarga (“Blue Eye”) is linked to the Islamic paramilitary Popular Defence Force. The most recent mining company to come to the area, Abersi, has suspected links to the RSF and actually started operations while protests were taking place, Fadul said.

Given their allegiance to the former regime, the gold mining companies were allowed to operate with impunity. On occasions the protests would induce companies such as the International Company to desist from mining, Fadul added, “but they would simply start again once the protests ended.” But with the transitional government now in place, local citizens feel more emboldened and harbour some hope for change. “From now on, we are not going to let his happen again,” said Ibrahim in Kalogi. “We are not going to let people just come and take our resources and leave us with death.”